You’re moody. Stressed. Hungry. And if you’re like many women, probably worried about gaining too much weight.

The trials and tribulations of pregnancy. 🙃

What’s more, you’re also overwhelmed by myriad conflicting opinions over what, how much, and when you should eat to maintain a healthy weight, stay satisfied, and nourish your growing baby.

A simple solution to most of these problems is to create a pregnancy meal plan. Not only does this make it easier to eat healthily during pregnancy, it also helps you avoid the postpartum weight gain that torments many new mothers.

In this article you’ll learn what a healthy pregnancy meal plan is, why you should follow one, what to include in a meal plan for pregnant women, and an example of a weekly pregnancy meal plan.

Table of Contents

+

What Is a Pregnancy Meal Plan?

A “meal plan” is a document that tells you exactly what and how much you’ll eat for every meal over a period of time, usually a single day.

A “pregnancy meal plan” is similar to a regular meal plan except that the food choices and amounts are optimized for a pregnant mother. That is, a pregnancy meal plan closely regulates the number of calories, quantity of each macronutrient, and types of foods you consume to ensure you and your child are as healthy as possible.

Pregnancy meal plans are useful because many women find that the stress and cravings accompanying pregnancy drive them to overeat and make unhealthy food choices, especially when they have to decide what to eat on the fly.

A pregnancy meal plan allows you to plan and prep your meals ahead of time, which minimizes the temptation to pig out on junk food and guarantees that you eat well-balanced meals to promote a healthy pregnancy.

Why Should I Follow a Healthy Pregnancy Meal Plan?

Gaining some weight during pregnancy is essential: it ensures your body has enough stored energy to support the healthy development of your child.

However, excessive “gestational weight gain” (weight gain during pregnancy) increases your risk of experiencing pregnancy- and labor-related complications, including hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, and C-section.

(This is particularly pertinent for women who begin pregnancy overweight [BMI ≥ 25] or obese [BMI ≥ 30] since they’re more likely to gain excess weight during pregnancy.)

It can also make returning to a healthy weight after you give birth more challenging. Research shows that women who gain excessive weight during pregnancy often find it difficult to shake the extra weight even years after they give birth.

Following a pregnancy meal plan helps you sidestep the health woes and weight struggles associated with excessive gestational weight gain because it makes regulating the number of calories and types of foods you eat easier. It also ensures that you consume sufficient vitamins, minerals, and other micronutrients, which research shows is a boon to the health of your baby.

In other words, following a pregnancy meal plan is an effective way to guarantee you and your baby stay as healthy as possible during and after the birth.

The Best Meal Plan for Pregnant Women

Every woman’s nutritional needs during pregnancy are different, which is why it’s a good idea to talk with a doctor or registered dietician before you commit to any pregnancy meal plan. That said, here are some solid “first principles” that work well for most people.

(And if you’d like even more specific advice about how many calories, how much of each macronutrient, and which foods you should eat to reach a healthy weight before you get pregnant or maintain a healthy weight while you’re pregnant, take the Legion Diet Quiz.)

Calories

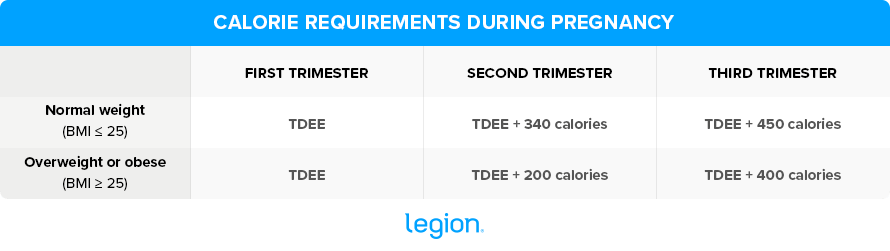

You don’t need to increase your calorie intake during the first trimester of pregnancy (the first 12 weeks). During the second and third trimesters, however, you’ll have to eat slightly more to meet your growing baby’s needs.

(Note: It’s best to avoid a calorie deficit during pregnancy because there isn’t sufficient evidence to show that it isn’t a risk to your baby. It might be fine or it might not, so it’s better to play it safe and eat enough to maintain your weight.)

To determine how many calories you should eat during each trimester, you first have to determine your total daily energy expenditure (TDEE), which is a mathematical estimate of how many total calories you burn throughout the day based on your weight, height, age, and activity level.

The best way to calculate your TDEE is to use the calculator here.

After calculating your TDEE, you can work out your calorie requirements for each trimester using this table:

Protein

Protein is essential for maintaining muscle mass and supporting fetal development, and your body’s demand for protein increases when you’re pregnant (especially during the last two trimesters).

Protein is also highly satiating, which means it helps you feel more satisfied by your meals. As a result, you’re less likely to overeat and experience excessive weight gain during pregnancy.

Eating a moderate-to-high-protein diet during pregnancy is a double-edged sword, though: while eating enough protein is healthy for you and your baby, eating too much may impair fetal development.

Thus, the “sweet spot” for most pregnant women is to get approximately 20% of their daily calories from protein, which works out to around 0.8 grams of protein per pound of bodyweight for most people.

Research shows this is enough to keep you and your baby healthy, but well below the level that might put your baby at risk.

Some healthy high-protein foods to include in your meal plan while pregnant are . . .

- Lean meats, such as sirloin steak, chicken breast, and pork loin

- Low-mercury fish, such as anchovies, herring, mackerel, salmon, sardines, tilapia, trout, and char

- Plant-based protein sources, such as beans and legumes, soy, and seitan

- Dairy products, such as Greek yogurt, cheese, cottage cheese, and milk

- Eggs

Carbohydrates

Your body breaks down the carbs you eat into glucose (blood sugar), which is your body’s primary source of energy.

To support the rapid growth of your child during pregnancy, your body’s demand for energy increases, which means you have to increase the amount of carbs you eat, too.

To ensure you hit your body’s energy demands during pregnancy, research shows that you should aim to get 45-to-60% of your daily calories from carbs.

Where possible, opt for low-GI, high-fiber carbs such as oats, rice, and grains; whole wheat bread and pasta; non-starchy vegetables like bell peppers, broccoli, and eggplant; and seeds, lentils, beans, and legumes.

Research shows these foods help you maintain stable blood sugar levels and a healthy weight during pregnancy, and lower your risk of preeclampsia.

Fat

There are four broad categories of dietary fat: monounsaturated fat, polyunsaturated fat, saturated fat, and trans fat.

Research shows that consuming adequate levels of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat (particularly omega-3 fatty acids) during pregnancy is essential for fetal development and minimizing the risk of birth complications. Specifically, it . . .

- Supports fetal brain, eye, and nervous system development

- Supports the development of the placenta

- Reduces the risk of preterm birth

- Reduces the risk of the child being born small for their gestational age

- Reduces the risk of pre- and postnatal depression

- May reduce the risk of preeclampsia

On the other hand, consuming large amounts of saturated fat and trans fat during pregnancy is associated with complications both before and after the birth, including an increased risk of . . .

- Preeclampsia

- Gestational diabetes

- Mental health and behavioral disorders

- Metabolic diseases later in the baby’s life

- Enlarged birth weight for the baby’s gestational age

For these reasons, research shows that you should get the remaining 20-to-35% of your daily calories from fat, but that less than 10% should come from saturated or trans fat.

The best sources of omega-3 fatty acids to include in your pregnancy meal plan are low-mercury fatty fish such as wild Alaskan salmon, char, Atlantic mackerel, and sardines.

And if you’re not fond of eating fish, get at least 400 mg of EPA and DHA per day from a supplement such as fish oil instead. (If you’re looking for a source of 100% natural, high-potency, molecularly distilled fish oil, check out Triton).

An Example Weekly Pregnancy Meal Plan

Here’s an example of a healthy weekly pregnancy meal plan. Keep in mind that this is an example and that your calorie and macronutrient requirements will likely differ.

(And again, if you’d like specific advice about how many calories, how much of each macronutrient, and which foods you should eat to reach a healthy weight before you’re pregnant or maintain a healthy weight while you’re pregnant, take the Legion Diet Quiz.)

Sunday:

- Breakfast: Blueberry Breakfast Quinoa

- Lunch: Korean Beef Bowl

- Snack: Maple Roasted Red Lentil Granola and Yogurt

- Dinner: Chicken Breasts with Black Bean Rice Pilaf and Roasted Asparagus

Monday (vegan):

- Breakfast: Vegan Breakfast Sandwich

- Lunch: Sweet Potato Bowl with Greens and Lentils

- Snack: Oatmeal and Berries

- Dinner: Tahini Turmeric and Tempeh Wrap with Sauteed Bok Choy

Tuesday:

- Breakfast: Sweet Potato Breakfast Hash

- Lunch: Chicken Tikka Kebabs and Steamed Broccoli

- Snack: Cottage Cheese and Pineapple

- Dinner: Lemony Lentil & Chickpea Salad

Wednesday:

- Breakfast: Greek Yogurt Goji Cereal Parfait

- Lunch: Roasted Vegetable and Balsamic Chicken Wrap

- Snack: Toast with Chocolate Hummus

- Dinner: 15-Minute Fish Tacos

Thursday:

- Breakfast: Cinnamon Bun Overnight Oats

- Lunch: Crockpot Chicken Caesar salad

- Snack: Apple and Peanut Butter

- Dinner: Salmon Quinoa Salad

Friday:

- Breakfast: Breakfast Pita with Egg, Feta, and Spinach

- Lunch: Deconstructed California Roll Salad

- Snack: Greek Yogurt and Berries

- Dinner: Fast & Healthy Chicken Parmesan

Saturday:

- Breakfast: Mexican Breakfast Casserole

- Lunch: Mediterranean Hummus Tuna Sandwich

- Snack: Nuts and Cheese Stick

- Dinner: 4-Ingredient Chicken & Rice Bowl with Steamed Veggies

FAQ #1: How much weight should I gain during pregnancy?

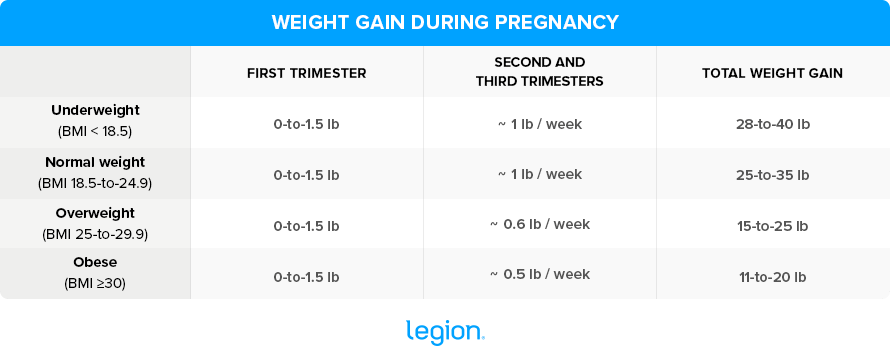

The amount of weight you should gain during pregnancy depends on which trimester you’re in and your starting BMI. Here are some guidelines that work for most people:

That said, some studies suggests that women who are obese should aim to gain even less than this.

Specifically, researchers propose the following weight gain targets for women who are obese:

- 30-to-34.9 BMI = 5.5-to-15 pounds of weight gain

- 35-to-39.9 BMI = 9.9 pounds or less of weight gain

- 40 BMI or higher = no weight gain

FAQ #2: Can I follow a vegetarian pregnancy meal plan?

Yes, you can follow a vegetarian pregnancy meal plan.

While not necessarily optimal, you can have a perfectly healthy pregnancy as a vegetarian as long as you ensure you meet your nutritional requirements for protein, omega-3 fatty acids, zinc, iodine, calcium, vitamin D, and vitamin B12.

Here are some tips that’ll help you do just that:

- Protein: Plant-based protein sources are less well-absorbed by the body and have weaker amino acid profiles than animal protein sources. You can largely overcome these shortcomings by combining plant-based protein sources in your meals (rice and beans, for example) and using a quality vegan protein powder (such as Plant+).

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: While some fatty acids are found in plants, they’re not easily converted into the types of fatty acids that confer health benefits in pregnant women. The easiest way to get around this is by supplementing with fish or algae oil. If you want a high-potency, molecularly distilled fish oil, try Triton.

- Zinc: Zinc is abundant in foods such as legumes, soy, nuts, seeds, and grains, so be sure to include plenty of these in your pregnancy meal plan. (If you’d like to keep your zinc levels topped off, try Triumph for women. It’s a 100% natural sport multivitamin that contains 30 mg of zinc along with 32 other ingredients to enhance health, performance, and mood; and reduce stress, fatigue, and anxiety.)

- Iodine: To increase your iodine intake, add seaweed to recipes like omelets, stir-fry dishes, and soups, season your meals with iodized salt instead of regular table salt, or take Triumph for women, which contains 225 mcg of iodine.

- Calcium: There are many vegetarian-friendly low-fat dairy products that’ll help you hit your calcium target, such as skyr, Greek yogurt, and cottage cheese made from pasteurized milk.

- Vitamin D: The best way to keep your D levels topped off is to spend time outdoors in the sun and to take a vitamin D supplement like Triumph for women that contains 2,000 IU of D per day.

- Vitamin B12: There are no plant sources of B12, so you’ll need to supplement in order to avoid a deficiency. (Triumph for women also contains 600 mcg of vitamin B12).

FAQ #3: Can I follow a vegan pregnancy meal plan?

Yes, you can follow a vegan pregnancy meal plan if you’re diligent about your nutritional intake. The above tips for vegetarians also apply for vegans.

However, because meeting your protein needs will likely be even more difficult, a plant-based protein powder might be necessary.

Additionally, since your diet also excludes dairy, you’ll want to up your intake of leafy, green vegetables like bok choy, collard greens, and kale to satisfy your calcium requirements.

FAQ #4: Should I follow a pregnancy diet meal plan?

Following a meal plan during pregnancy can help you meet your macronutrient and micronutrient needs while avoiding excessive gestational weight gain.

It’s worth noting, though, that there isn’t sufficient evidence to warrant calorie restriction during pregnancy, as it may jeopardize the health of your baby. If you’re obese and considering dieting while pregnant, talk with your doctor to discuss the best course of action. In general, you’ll probably want to reach a healthy weight before you get pregnant.

FAQ #5: Can I start dieting after giving birth?

There isn’t enough research to know for sure whether dieting postpartum (after giving birth) is entirely without risk, though most of the research we currently have suggests that restricting your calories postpartum is safe provided you aren’t underweight or malnourished and consume a healthy diet that’s rich in vitamins and minerals.

That said, there are several factors that you should consider before you start dieting postpartum.

For example, several muscles such as your abdominals need to recover after giving birth. Research shows that eating in a calorie deficit impairs your body’s ability to repair muscle tissue, which could elongate your post-birth recovery.

What’s more, breastfeeding increases calorie demands by up to 500 calories per day. If you don’t factor this into your diet, you may reduce the quantity and quality of your breastmilk, which could have negative repercussions for your baby.

Also bear in mind that breastfeeding mothers tend to lose weight as a matter of course. Thus, if you decide to breastfeed, there’s a good chance you’ll lose weight without the need to diet.

Scientific References +

- Asefa, F., & Nemomsa, D. (2016). Gestational weight gain and its associated factors in Harari Regional State: Institution based cross-sectional study, Eastern Ethiopia. Reproductive Health, 13(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12978-016-0225-X/TABLES/5

- Wang, L., Zhang, X., Chen, T., Tao, J., Gao, Y., Cai, L., Chen, H., & Yu, C. (2021). Association of Gestational Weight Gain With Infant Morbidity and Mortality in the United States. JAMA Network Open, 4(12), e2141498–e2141498. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2021.41498

- Asefa, F., Cummins, A., Dessie, Y., Hayen, A., & Foureur, M. (2020). Gestational weight gain and its effect on birth outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 15(4), e0231889. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0231889

- Kominiarek, M. A., & Peaceman, A. M. (2017). Gestational Weight Gain. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 217(6), 642. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AJOG.2017.05.040

- Artal, R., Catanzaro, R. B., Gavard, J. A., Mostello, D. J., & Friganza, J. C. (2007). A lifestyle intervention of weight-gain restriction: diet and exercise in obese women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism = Physiologie Appliquee, Nutrition et Metabolisme, 32(3), 596–601. https://doi.org/10.1139/H07-024

- Davis, A. M. (2015). Pandemic of Pregnant Obese Women: Is It Time to Re-Evaluate Antenatal Weight Loss? Healthcare, 3(3), 733. https://doi.org/10.3390/HEALTHCARE3030733

- Nuttall, F. Q. (2015). Body Mass Index: Obesity, BMI, and Health: A Critical Review. Nutrition Today, 50(3), 117. https://doi.org/10.1097/NT.0000000000000092

- Deputy, N. P., Sharma, A. J., Kim, S. Y., & Hinkle, S. N. (2015). Prevalence and Characteristics Associated With Gestational Weight Gain Adequacy. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 125(4), 773. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000739

- Nehring, I., Schmoll, S., Beyerlein, A., Hauner, H., & Von Kries, R. (2011). Gestational weight gain and long-term postpartum weight retention: a meta-analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 94(5), 1225–1231. https://doi.org/10.3945/AJCN.111.015289

- Borge, T. C., Aase, H., Brantsæter, A. L., & Biele, G. (2017). The importance of maternal diet quality during pregnancy on cognitive and behavioural outcomes in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 7(9). https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2017-016777

- Blomberg, M. (2011). Maternal and neonatal outcomes among obese women with weight gain below the new Institute of Medicine recommendations. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 117(5), 1065–1070. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0B013E318214F1D1

- Weight Gain During Pregnancy | Pregnancy | Maternal and Infant Health | CDC. (n.d.). Retrieved March 9, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-weight-gain.htm#trackers

- Parrettini, S., Caroli, A., & Torlone, E. (2020). Nutrition and Metabolic Adaptations in Physiological and Complicated Pregnancy: Focus on Obesity and Gestational Diabetes. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 11, 937. https://doi.org/10.3389/FENDO.2020.611929/BIBTEX

- Koletzko, B., Godfrey, K. M., Poston, L., Szajewska, H., Van Goudoever, J. B., De Waard, M., Brands, B., Grivell, R. M., Deussen, A. R., Dodd, J. M., Patro-Golab, B., & Zalewski, B. M. (2019). Nutrition During Pregnancy, Lactation and Early Childhood and its Implications for Maternal and Long-Term Child Health: The Early Nutrition Project Recommendations. Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism, 74(2), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496471

- Weigle, D. S., Breen, P. A., Matthys, C. C., Callahan, H. S., Meeuws, K. E., Burden, V. R., & Purnell, J. Q. (2005). A high-protein diet induces sustained reductions in appetite, ad libitum caloric intake, and body weight despite compensatory changes in diurnal plasma leptin and ghrelin concentrations. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 82(1), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN.82.1.41

- Westerterp-Plantenga, M. S. (2003). The significance of protein in food intake and body weight regulation. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 6(6), 635–638. https://doi.org/10.1097/00075197-200311000-00005

- Ortinau, L. C., Hoertel, H. A., Douglas, S. M., & Leidy, H. J. (2014). Effects of high-protein vs. high- fat snacks on appetite control, satiety, and eating initiation in healthy women. Nutrition Journal, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-13-97

- Herring, C. M., Bazer, F. W., Johnson, G. A., & Wu, G. (2018). Impacts of maternal dietary protein intake on fetal survival, growth, and development. Experimental Biology and Medicine, 243(6), 525. https://doi.org/10.1177/1535370218758275

- Kominiarek, M. A., & Rajan, P. (2016). Nutrition Recommendations in Pregnancy and Lactation. The Medical Clinics of North America, 100(6), 1199. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MCNA.2016.06.004

- Mousa, A., Naqash, A., & Lim, S. (2019). Macronutrient and Micronutrient Intake during Pregnancy: An Overview of Recent Evidence. Nutrients, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/NU11020443

- Hull, H. R., Herman, A., Gibbs, H., Gajewski, B., Krase, K., Carlson, S. E., Sullivan, D. K., & Goetz, J. (2020). The effect of high dietary fiber intake on gestational weight gain, fat accrual, and postpartum weight retention: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12884-020-03016-5/TABLES/5

- Coletta, J. M., Bell, S. J., & Roman, A. S. (2010). Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Pregnancy. Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 3(4), 163. https://doi.org/10.3909/riog0137

- Duttaroy, A. K., & Basak, S. (2020). Maternal dietary fatty acids and their roles in human placental development. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids, 155. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PLEFA.2020.102080

- De Seymour, J. V., Simmonds, L. A., Gould, J., Makrides, M., & Middleton, P. (2019). Omega-3 fatty acids to prevent preterm birth: Australian pregnant women’s preterm birth awareness and intentions to increase omega-3 fatty acid intake. Nutrition Journal, 18(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12937-019-0499-2/TABLES/4

- Martínez-Galiano, J. M., Olmedo-Requena, R., Barrios-Rodríguez, R., Amezcua-Prieto, C., Bueno-Cavanillas, A., Salcedo-Bellido, I., Jimenez-Moleon, J. J., & Delgado-Rodríguez, M. (2018). Effect of Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet and Olive Oil Intake during Pregnancy on Risk of Small for Gestational Age Infants. Nutrients, 10(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/NU10091234

- Oken, E., Ning, Y., Rifas-Shiman, S. L., Rich-Edwards, J. W., Olsen, S. F., & Gillman, M. W. (2007). Diet during pregnancy and risk of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension. Annals of Epidemiology, 17(9), 663–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ANNEPIDEM.2007.03.003

- Spracklen, C. N., Smith, C. J., Saftlas, A. F., Robinson, J. G., & Ryckman, K. K. (2014). Maternal hyperlipidemia and the risk of preeclampsia: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 180(4), 346–358. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJE/KWU145

- Jin, W. Y., Lin, S. L., Hou, R. L., Chen, X. Y., Han, T., Jin, Y., Tang, L., Zhu, Z. W., & Zhao, Z. Y. (2016). Associations between maternal lipid profile and pregnancy complications and perinatal outcomes: A population-based study from China. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12884-016-0852-9/TABLES/5

- Sullivan, E. L., Nousen, E. K., & Chamlou, K. A. (2014). Maternal high fat diet consumption during the perinatal period programs offspring behavior. Physiology & Behavior, 123, 236–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSBEH.2012.07.014

- Mennitti, L. V., Oliveira, J. L., Morais, C. A., Estadella, D., Oyama, L. M., Oller do Nascimento, C. M., & Pisani, L. P. (2015). Type of fatty acids in maternal diets during pregnancy and/or lactation and metabolic consequences of the offspring. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 26(2), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JNUTBIO.2014.10.001

- Vrijkotte, T. G. M., Krukziener, N., Hutten, B. A., Vollebregt, K. C., Van Eijsden, M., & Twickler, M. B. (2012). Maternal lipid profile during early pregnancy and pregnancy complications and outcomes: the ABCD study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 97(11), 3917–3925. https://doi.org/10.1210/JC.2012-1295

- Koletzko, B., Lien, E., Agostoni, C., Böhles, H., Campoy, C., Cetin, I., Decsi, T., Dudenhausen, J. W., Dupont, C., Forsyth, S., Hoesli, I., Holzgreve, W., Lapillonne, A., Putet, G., Secher, N. J., Symonds, M., Szajewska, H., Willatts, P., & Uauy, R. (2008). The roles of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in pregnancy, lactation and infancy: review of current knowledge and consensus recommendations. Journal of Perinatal Medicine, 36(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1515/JPM.2008.001

- Koletzko, B., Godfrey, K. M., Poston, L., Szajewska, H., Van Goudoever, J. B., De Waard, M., Brands, B., Grivell, R. M., Deussen, A. R., Dodd, J. M., Patro-Golab, B., & Zalewski, B. M. (2019). Nutrition During Pregnancy, Lactation and Early Childhood and its Implications for Maternal and Long-Term Child Health: The Early Nutrition Project Recommendations. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 74(2), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496471

- Parrettini, S., Caroli, A., & Torlone, E. (2020). Nutrition and Metabolic Adaptations in Physiological and Complicated Pregnancy: Focus on Obesity and Gestational Diabetes. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 11, 937. https://doi.org/10.3389/FENDO.2020.611929/BIBTEX

- Sebastiani, G., Barbero, A. H., Borrás-Novel, C., Casanova, M. A., Aldecoa-Bilbao, V., Andreu-Fernández, V., Tutusaus, M. P., Martínez, S. F., Roig, M. D. G., & García-Algar, O. (2019). The Effects of Vegetarian and Vegan Diet during Pregnancy on the Health of Mothers and Offspring. Nutrients, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/NU11030557

- van Vliet, S., Burd, N. A., & van Loon, L. J. C. (2015). The Skeletal Muscle Anabolic Response to Plant- versus Animal-Based Protein Consumption. The Journal of Nutrition, 145(9), 1981–1991. https://doi.org/10.3945/JN.114.204305

- Kimball, S. R., & Jefferson, L. S. (2006). Signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms through which branched-chain amino acids mediate translational control of protein synthesis. The Journal of Nutrition, 136(1 Suppl). https://doi.org/10.1093/JN/136.1.227S

- Sebastiani, G., Barbero, A. H., Borrás-Novel, C., Casanova, M. A., Aldecoa-Bilbao, V., Andreu-Fernández, V., Tutusaus, M. P., Martínez, S. F., Roig, M. D. G., & García-Algar, O. (2019). The Effects of Vegetarian and Vegan Diet during Pregnancy on the Health of Mothers and Offspring. Nutrients, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/NU11030557

- Dusdieker, L. B., Hemingway, D. L., & Stumbo, P. J. (1994). Is milk production impaired by dieting during lactation? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 59(4), 833–840. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/59.4.833

- Mohammad, M. A., Sunehag, A. L., & Haymond, M. W. (2009). Effect of dietary macronutrient composition under moderate hypocaloric intake on maternal adaptation during lactation. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89(6), 1821. https://doi.org/10.3945/AJCN.2008.26877

- Fukano, M., Tsukahara, Y., Takei, S., Nose-Ogura, S., Fujii, T., & Torii, S. (2021). Recovery of Abdominal Muscle Thickness and Contractile Function in Women after Childbirth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH18042130

- Berihun, S., Kassa, G. M., & Teshome, M. (2017). Factors associated with underweight among lactating women in Womberma woreda, Northwest Ethiopia; A cross-sectional study. BMC Nutrition, 3(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/S40795-017-0165-Z/TABLES/4

- Jarlenski, M. P., Bennett, W. L., Bleich, S. N., Barry, C. L., & Stuart, E. A. (2014). Effects of breastfeeding on postpartum weight loss among U.S. women. Preventive Medicine, 69, 146. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YPMED.2014.09.018

- Sámano, R., Martínez-Rojano, H., Martínez, E. G., Jiménez, B. S., Rodríguez, G. P. V., Zamora, J. P., & Casanueva, E. (2013). Effects of breastfeeding on weight loss and recovery of pregestational weight in adolescent and adult mothers. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 34(2), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482651303400201

- Janney, C. A., Zhang, D., & Sowers, M. (1997). Lactation and weight retention. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 66(5), 1116–1124. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/66.5.1116