It’s estimated that there are over 2+ million scientific papers published each year, and this firehose only seems to intensify.

Even if you narrow your focus to fitness research, it would take several lifetimes to unravel the hairball of studies on nutrition, training, supplementation, and related fields.

This is why my team and I spend thousands of hours each year dissecting and describing scientific studies in articles, podcasts, and books and using the results to formulate our 100% all-natural sports supplements and inform our coaching services.

And while the principles of proper eating and exercising are simple and somewhat immutable, reviewing new research can reinforce or reshape how we eat, train, and live for the better.

Thus, each week, I’m going to share three scientific studies on diet, exercise, supplementation, mindset, and lifestyle that will help you gain muscle and strength, lose fat, perform and feel better, live longer, and get and stay healthier.

This week, you’ll learn whether getting stronger on the deadlift improves your squat and vice versa, the best way to take creatine, and how sleep impacts weight loss.

Getting stronger at deadlifting makes you stronger at squatting and vice versa.

Source: “A Comparison Between the Squat and the Deadlift for Lower Body Strength and Power Training” published on July 21, 2020 in Journal of Human Kinetics.

The squat and the deadlift train many of the same muscles—especially the glutes, spinal erectors, and the quads (to a lesser extent)—so it’s reasonable to assume that getting better at one would also bring up the other.

How close is this relationship, though?

For example, if you improve your deadlift by 50 pounds, does this boost your squat by 50 pounds? Or 40 pounds? Ten pounds?

And is the reverse also true? Does boosting your squat benefit your deadlift?

It’s questions like these that scientists at the University of Bologna sought to answer in this study.

The researchers split 25 experienced male weightlifters into a deadlift group and a squat group.

Aside from some leg extensions, these were the only heavy lower-body exercises both groups performed throughout the study. Thus, the deadlift group did zero squatting, and the squatting group did zero deadlifting.

Otherwise, both groups followed the same program: they both trained 3 times per week and did a variety of upper body exercises including the barbell row, lat pulldown, flat and incline bench press, overhead press, lateral raise, overhead triceps extension, barbell curl, and upright row.

The results showed that the deadlift group increased their deadlift one-rep max by ~18% (from ~310 lb to ~365 lb) and their squat one-rep max by ~5% (~337 lb to ~353 lb).

The squat group increased their squat one-rep max by ~13% (~273 lb to ~310 lb) and their deadlift one-rep max by ~7% (~284 lb to ~304 lb).

Put differently, for every pound these folks added to their deadlift, their squat improved by about ¼ pound. And for every pound they added to their squat, their deadlift increased by about ½ a pound.

This squares with what I’ve found in my own training and what I’ve gleaned from other experienced powerlifters:

- Although training specificity is king (the best way to get better at any exercise is to do it more), there is some carryover between exercises that train similar muscle groups. This is one of the reasons I advocate periodically rotating between different exercises—it trains your muscles more completely, reduces the risk of overuse injuries, and enlivens your workouts.

- Improving your squat generally boosts your deadlift more than improving your deadlift boosts your squat, but you should do both if you want to gain as much muscle and strength as possible. Case in point: it’s easy to find weightlifters who can deadlift in the 400s but only squat in the 300s, but you won’t find many folks squatting in the 400s who can only deadlift in the 300s.

This study is also an unintentional cautionary tale about the dangers of increasing your training volume too quickly. Although the researchers considered these folks “experienced,” they’d only been lifting weights for three years and were probably closer to “intermediates” according to a strength standards chart (most of them were squatting and deadlifting in the high 200s or low 300s).

These intermediates were then thrust into a workout routine that would have crushed most advanced weightlifters: 5 sets of 4-to-10 reps of 11 different exercises 3 times per week—165 sets per week. (For reference, my Beyond Bigger Leaner Stronger program for advanced weightlifters involves just 80 sets per week spread across 5 workouts).

Unsurprisingly, 3 out of the 14 weightlifters in the deadlifting group had to throw in the towel after injuring their lower backs after just 6 weeks.

Deadlifts aren’t inherently bad for your back, but doing too much of any exercise is a first-class ticket to snap city. If the study had been longer, it’s likely both groups would have seen more casualties.

The best way to avoid this is to simply follow a science-based strength training routine, like one of mine. 🙂 Specifically, if you’re looking for a strength training program that includes the right amount of deadlifting and squatting to build muscle and stay injury-free, check out my fitness books Bigger Leaner Stronger for men, and Thinner Leaner Stronger for women.

(Or if you aren’t sure if Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger are right for you or if another training program might be a better fit for your circumstances and goals, then take the Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

TL;DR: Improving your squat will improve your deadlift and vice versa, but you should still do both exercises to gain as much muscle and strength as possible.

You don’t need to take creatine every day to get the benefits.

Source: “Muscle creatine loading in men” published on February 1, 1996 in Journal of Applied Physiology (1985).

Unlike caffeine and most other performance-enhancing supplements, you need to take creatine consistently for a week or more before you notice significant benefits. In fact, you generally need to take about ~3-to-5 grams per day for several weeks to maximize its effects.

Many people assume that once you’ve fully saturated your muscles with creatine, you need to keep taking it every day to prevent your creatine stores from quickly being depleted.

Is this really necessary, though?

After all, if creatine takes weeks to build up in your system, doesn’t it stand to reason that it would probably take at least as long for your levels to drop?

In other words, does skipping a dose here and there negatively impact your training, or is supplementing with creatine more like charging your phone—something you do periodically but not necessarily every day?

To answer this question, scientists at Queen’s Medical Centre split 24 active male participants into 3 groups:

- Group 1 took 20 g of creatine per day for 6 days (referred to as creatine “loading”) and then stopped taking it completely for the next 28 days.

- Group 2 took 20 g of creatine per day for 6 days then 2 g per day for the following 28 days.

- Group 3 took 3 g of creatine per day for 28 days.

(Technically, there were 31 participants split into 4 groups, but the fourth group just underwent some arcane creatine metabolism tests that aren’t relevant to this discussion.)

The results showed that both groups that took 20 g of creatine per day increased the creatine concentration in their muscles by ~20% after just 6 days.

The guys in group 2 maintained this increase for the entire study by taking a daily dose of 2 g, whereas the guys in group 1 (who stopped taking creatine after loading it) experienced a gradual decline in creatine levels. After 2 weeks, their creatine levels had dropped by ~4% from ~145 mmol/kg dry mass (dm) to ~139 mmol/kg dm, and after another 2 weeks, their creatine levels had essentially returned to baseline (~123 mmol/kg dm).

The participants in group 3 experienced a similar 20%-increase in creatine levels, but it took about 4 weeks to achieve this since they didn’t “load” their muscles like the other two groups.

The first takeaway from this study is that missing a dose of creatine here and there isn’t a big deal. After stopping creatine supplementation cold turkey for 2 weeks, the guys in this study still had about 80% of the newly-acquired creatine left in their muscles, and it took another 2 weeks for their creatine levels to return to what they were before they started supplementing.

Thus, don’t sweat if you forget to take creatine occasionally—your muscles won’t miss it.

Based on this, it’s also logical to assume that if you miss a few doses of creatine (maybe you’re out of town for a few days and don’t feel like bringing a little baggie of white powder through airport security), you can easily “catch up” your creatine levels by taking a larger dose over the next few days. A “mini creatine load,” basically.

For example, if you normally take 5 g of creatine per day but don’t take it for 3 days, you can probably bring your levels back to where they were before by taking 10 g per day over the next 3 days.

Second, taking 20 g of creatine per day for about a week will help you top off your creatine levels quickly, which you can then maintain with a significantly lower dose. In this study, that lower dose was 2 g per day, but most evidence shows that this is an absolute minimum and it’s better to take 3-to-5 g per day to maximize your creatine stores.

Finally, if you don’t want to “load” creatine, this study shows that you can get the same benefits by taking a smaller dose over a longer period of time.

And if you want a 100% natural post-workout drink that contains 5 g of micronized creatine monohydrate in every serving, try Recharge.

(Or if you aren’t sure if Recharge is right for you or if another supplement might be a better fit for your budget, circumstances, and goals, then take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz! In less than a minute, it’ll tell you exactly what supplements are right for you. Click here to check it out.)

TL;DR: You don’t need to take creatine every day so long as your average intake is about 3-to-5 g per day over time. If you don’t take it for several days, you can probably “catch up” by taking a larger dose the next few days.

Getting sufficient sleep helps you lose fat.

Source: “Effect of Sleep Extension on Objectively Assessed Energy Intake Among Adults With Overweight in Real-life Settings: A Randomized Clinical Trial” published on February 7, 2022 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Sleep bears up on your body weight more than most people realize. Studies show that for every hour you sleep less than 7 hours each night, your risk of obesity increases by 9% (sleeping 5 hours per night raises your risk by 27%, for instance).

What’s more, research shows that insufficient sleep disrupts the hormones that regulate appetite, making you more likely to overeat and crave and snack on unhealthy foods.

Sleeping too little plays havoc with muscle gain, too. Studies show it depresses muscle protein synthesis rates, increases muscle loss and decreases fat loss, and musses up anabolic (muscle-building) hormone levels, collectively making muscle building more challenging.

In other words, we know that not sleeping enough makes achieving your weight-loss and body-composition goals more difficult, but does that mean sleeping more makes fat loss easier? That’s the question scientists at The University of Chicago wanted to answer in this study.

The researchers recruited 80 overweight participants (41 men and 39 women) aged between 21 and 40 years old, who were free from any medical issues that might disrupt their sleep, regularly slept less than 6.5 hours per night, and worked a job that didn’t interfere with their habitual sleep pattern (no shift work).

For two weeks, the participants recorded when they got into and out of bed and wore activity trackers so that the researchers could track their sleep habits. This allowed the researchers to calculate the participants’ sleep duration and total time spent in bed.

After 2 weeks, the researchers split the participants into 2 groups: A sleep-extension group and a control group. The sleep-extension group received sleep hygiene coaching designed to help them sleep 2 hours longer each night, and the control group continued to live as usual. After a week, the participants in the sleep-extension group received more sleep counseling if they needed it.

The researchers didn’t control the participants’ diets, but they measured their calorie intake in a roundabout way.

They did this by first measuring how many calories the participants burned using doubly labeled water—an accurate method of measuring metabolic rate by having someone drink water containing isotopes, then measuring how many of the isotopes the body excretes over time.

They also measured the participants’ resting metabolic rate while fasted and fed and the thermic effect of the food the participants ate using indirect calorimetry, which involves capturing and analyzing the gasses people breathe out to estimate calorie expenditure.

Finally, the researchers asked the participants to weigh themselves twice every morning while nude and before eating or drinking anything (the researchers recorded these weighings, but the participants were never privy to the results) and measured the participants’ body composition using a DEXA scanner at the beginning, middle, and end of the study.

All of this data enabled the researchers to compare energy expenditure with changes in body composition over time and estimate the participants’ calorie intake.

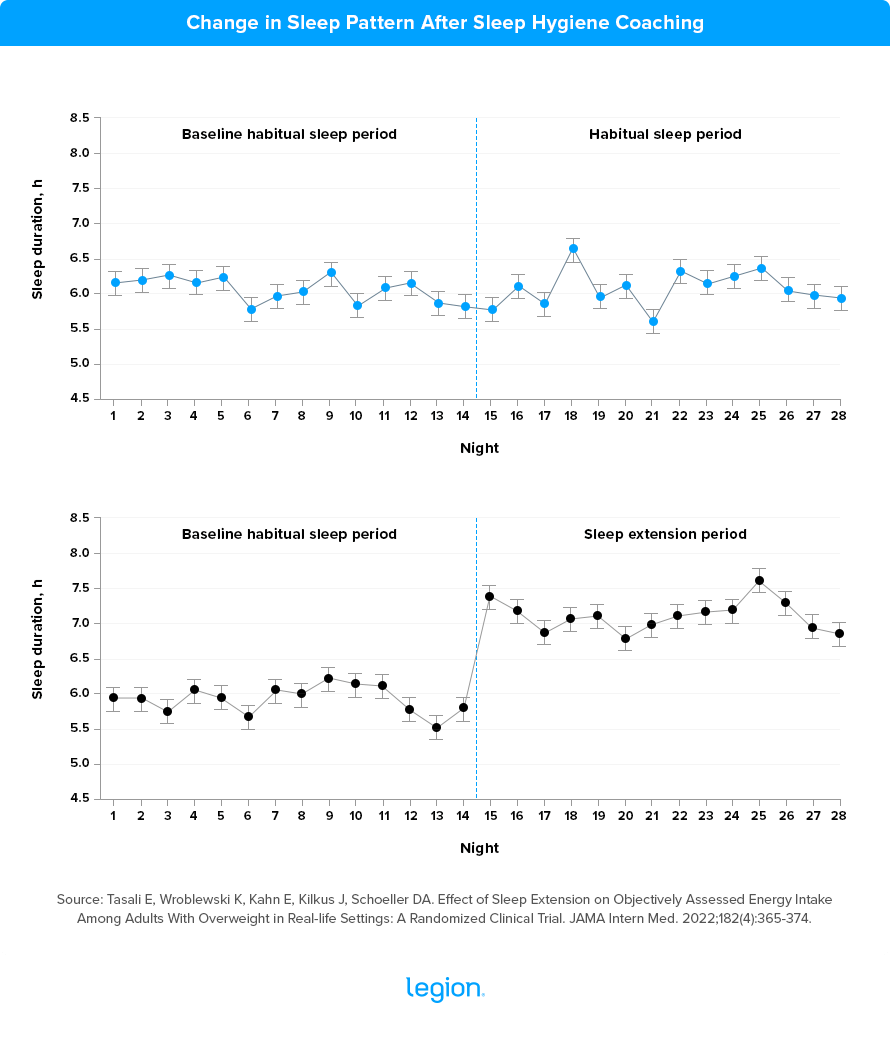

The results showed that coaching people on the importance of sleep hygiene significantly increased the amount of time they spent sleeping. Here’s a graph showing how each group slept over the course of the study:

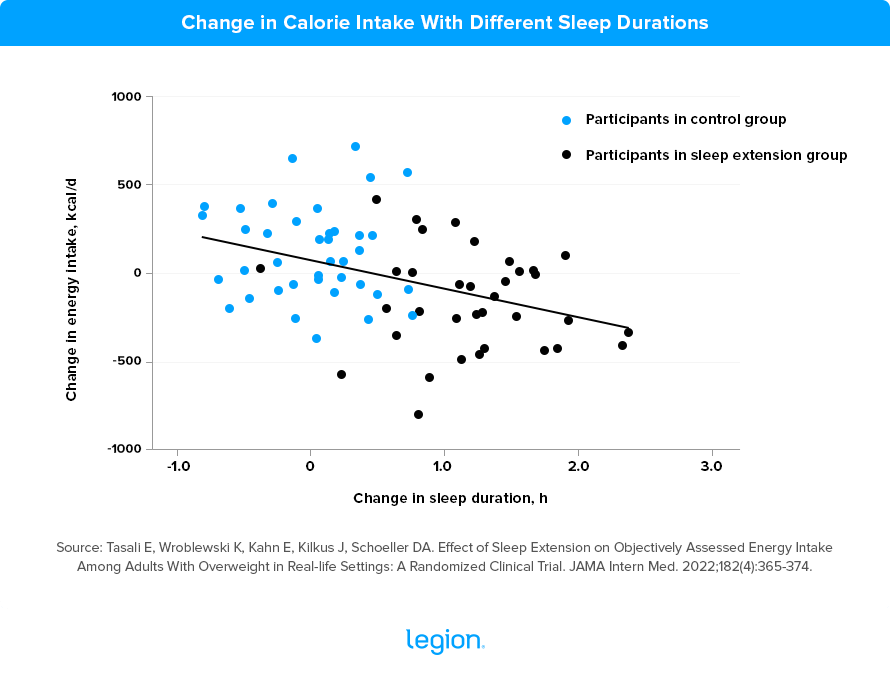

The results also showed that those who slept more ate less. On average, people in the sleep-extension group consumed ~270 fewer calories than those in the control group, and for every extra hour that they spent sleeping, they decreased their calorie intake by ~162 calories per day. Conversely, the control group consumed slightly more daily calories as the study progressed. Here’s a graph to illustrate:

Neither group saw a change in how many calories they burned per day. However, because participants in the sleep-extension group consumed fewer calories than normal, they put themselves into a calorie deficit and lost a small amount of weight (~0.8 lb), mostly from fat-free mass (presumably water). While this weight loss was slight, the study only lasted 2 weeks. If the same rate of weight loss continued, the researchers predicted that it would add up to a 26-lb. weight loss over 3 years.

On the other hand, because the control group increased their calorie intake slightly but burned no extra calories, they gained a small amount of weight (~0.6 lb).

These results are of a piece with the mountain of evidence showing how important sleep is for improving your body composition. If you want to lose weight, try to get 7-to-9 hours of sleep per night.

If you find nodding off tough, try the science-proven sleep hygiene techniques in this article:

7 Proven Ways to Sleep Better Than Ever Before

Or if you’d like to try a 100% natural sleep supplement that helps you fall asleep faster, stay asleep longer, and wake up feeling more rested, try Lunar.

TL;DR: Sleep at least 7 hours per night to consume fewer calories throughout the day and lose fat faster.

Scientific References +

- Nigro, F., & Bartolomei, S. (2020). A Comparison Between the Squat and the Deadlift for Lower Body Strength and Power Training. Journal of Human Kinetics, 73(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.2478/HUKIN-2019-0139

- Gamble, P. P. C. (n.d.). Implications and Applications of Training Specificity for Co... : Strength & Conditioning Journal. Retrieved August 24, 2022, from https://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/Abstract/2006/06000/Implications_and_Applications_of_Training.9.aspx

- Hultman, E., Söderlund, K., Timmons, J. A., Cederblad, G., & Greenhaff, P. L. (1996). Muscle creatine loading in men. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 81(1), 232–237. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPL.1996.81.1.232

- Naderi, A., Oliveira, E. P. de, Ziegenfuss, T. N., & Willems, M. E. T. (2016). Timing, optimal dose and intake duration of dietary supplements with evidence-based use in sports nutrition. Journal of Exercise Nutrition & Biochemistry, 20(4), 1. https://doi.org/10.20463/JENB.2016.0031

- Kreider, R. B., Kalman, D. S., Antonio, J., Ziegenfuss, T. N., Wildman, R., Collins, R., Candow, D. G., Kleiner, S. M., Almada, A. L., & Lopez, H. L. (2017). International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 2017 14:1, 14(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12970-017-0173-Z

- Wax, B., Kerksick, C. M., Jagim, A. R., Mayo, J. J., Lyons, B. C., & Kreider, R. B. (2021). Creatine for Exercise and Sports Performance, with Recovery Considerations for Healthy Populations. Nutrients 2021, Vol. 13, Page 1915, 13(6), 1915. https://doi.org/10.3390/NU13061915

- Bemben, M. G., & Lamont, H. S. (2005). Creatine supplementation and exercise performance: recent findings. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 35(2), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200535020-00002

- Tasali, E., Wroblewski, K., Kahn, E., Kilkus, J., & Schoeller, D. A. (2022). Effect of Sleep Extension on Objectively Assessed Energy Intake Among Adults With Overweight in Real-life Settings: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Internal Medicine, 182(4), 365–374. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAINTERNMED.2021.8098

- Zhou, Q., Zhang, M., & Hu, D. (2019). Dose-response association between sleep duration and obesity risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Sleep and Breathing 2019 23:4, 23(4), 1035–1045. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11325-019-01824-4

- Fenton, S., Burrows, T. L., Skinner, J. A., & Duncan, M. J. (2021). The influence of sleep health on dietary intake: a systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 34(2), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/JHN.12813

- Zhu, B., Shi, C., Park, C. G., Zhao, X., & Reutrakul, S. (2019). Effects of sleep restriction on metabolism-related parameters in healthy adults: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 45, 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SMRV.2019.02.002

- Saner, N. J., Lee, M. J. C., Pitchford, N. W., Kuang, J., Roach, G. D., Garnham, A., Stokes, T., Phillips, S. M., Bishop, D. J., & Bartlett, J. D. (2020). The effect of sleep restriction, with or without high-intensity interval exercise, on myofibrillar protein synthesis in healthy young men. The Journal of Physiology, 598(8), 1523–1536. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP278828

- Nedeltcheva, A. V., Kilkus, J. M., Imperial, J., Schoeller, D. A., & Penev, P. D. (2010). Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity. Annals of Internal Medicine, 153(7), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-153-7-201010050-00006

- Chennaoui, M., Drogou, C., Sauvet, F., Gomez-Merino, D., Scofield, D. E., & Nindl, B. C. (2014). Effect of acute sleep deprivation and recovery on Insulin-like Growth Factor-I responses and inflammatory gene expression in healthy men. European Cytokine Network, 25(3), 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1684/ECN.2014.0356