Key Takeaways

- Muscle hypertrophy refers to an increase in the size of muscle cells, and hypertrophy training refers to resistance training meant to maximize muscle hypertrophy.

- The single best way to stimulate muscle hypertrophy is to get stronger.

- Keep reading to learn the best exercises, workout routines, and dietary techniques to maximize muscle hypertrophy.

Muscle hypertrophy is a complex subject, and if you’re reading this article, you probably have three questions:

- How do you say it?

- What does it mean?

- How do you maximize it?

The first two questions are simple enough to answer—you pronounce it hi-PUR-trophy, and it’s the technical term for muscle growth.

The third question, however, will require a bit of explanation because many people have many opinions on how to eat and train for maximum muscle growth.

Some say the key is using different rep ranges to better stimulate different muscle fibers.

Others claim there are two kinds of muscle hypertrophy—“myofibrillar” and “sarcoplasmic”—and you should strive for both in your training if you want to get jacked.

And then there are those who say that the primary factor in muscle hypertrophy is your genes, and if you don’t have the right DNA, you’ll never gain much muscle regardless of how you eat, train, or supplement.

If this has you feeling muddled, I understand. I’ve been there.

When I started working out, I was your average tall, skinny dude, and for the first one and a half years, I followed run-of-the-mill bodybuilding magazine workouts billed as “hypertrophy training.”

Thanks to “newbie gains,” it worked . . . kind of. By the end of this period I was, uh, a little less skinny, I guess?

Let’s fast-forward about five and a half years.

By now, I’d gained a fair amount of muscle–25 pounds or so—but far less than what you’d expect from seven years of dedicated weightlifting.

Soon after that last picture was taken, I decided to educate myself on the real science of hypertrophy training (and eating) and implement what I had learned.

And here’s where I am now:

View this post on Instagram

As you can imagine, I’ve learned a trick or two along the way about how to get bigger, leaner, and stronger, and in this article, I’ll share with you the key lessons so you can follow in my footsteps.

Let’s get to it.

Would you rather listen to this article? Click the play button below!

Want to listen to more stuff like this? Check out my podcast!

What Is Muscle Hypertrophy?

Muscle hypertrophy is the scientific term for an increase in muscle size.

Hyper means “over or more,” and trophy means “growth,” so muscle hypertrophy literally means the growth of muscle cells.

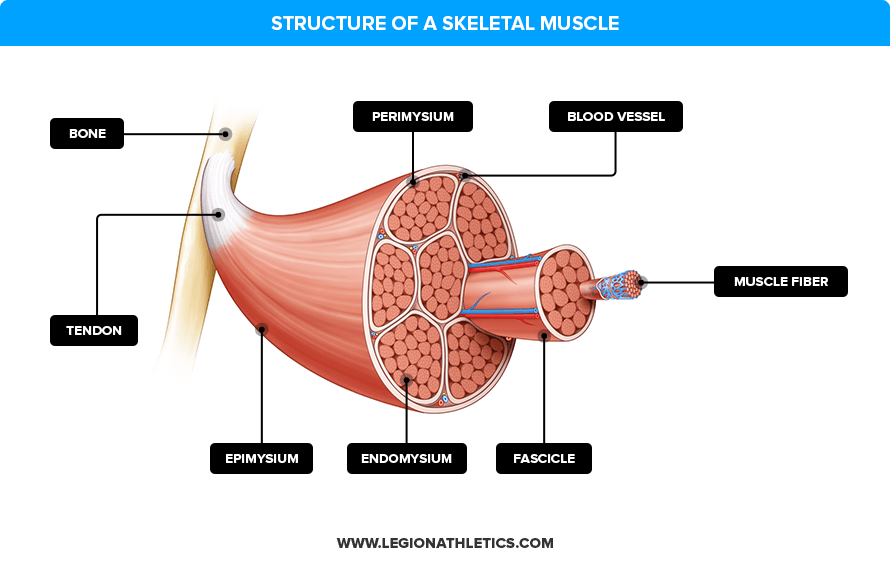

To understand what causes muscle hypertrophy and how it works, you first need to understand what muscles are composed of.

Muscle tissue is a complex structure, with bundles of long strands of muscle cells sheathed in a thick band of connective tissue known as the perimysium.

Here’s how it looks:

The three main components of muscle tissue are:

- Water, which makes up about 60-to-80% of muscle tissue by weight. (Want to be creeped out? Read how scientists discovered this.)

- Glycogen, which is a form of stored carbohydrate that can make up 0-to-5% of muscle tissue by weight.

- Protein, which makes up about 20% of muscle tissue by weight.

Theoretically, an increase in any of these three components would qualify as “muscle hypertrophy,” but the one weightlifters are most interested in is the third element:

An increase in the amount of protein in the muscle.

This is known as myofibrillar hypertrophy (myo means “muscle,” and a fibril is a threadlike cellular structure).

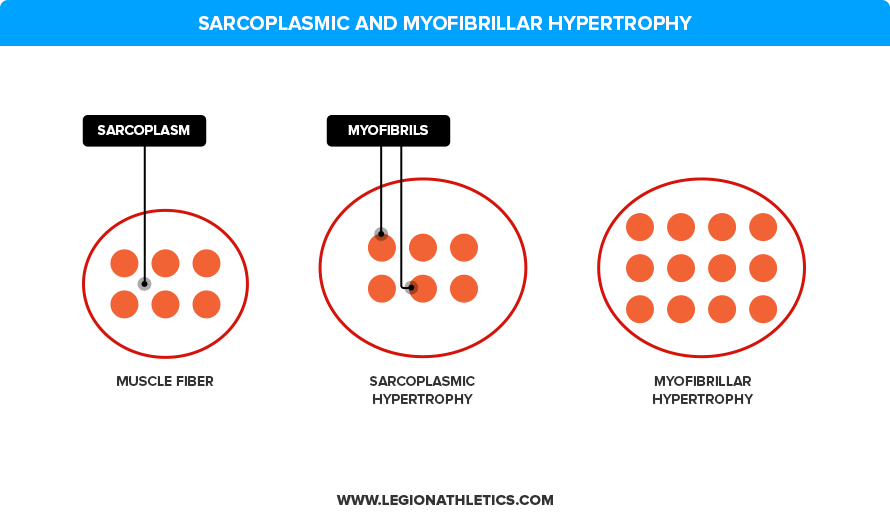

Earlier in this article, I mentioned another type of muscle hypertrophy: sarcoplasmic hypertrophy.

Sarco means “flesh” and plasmic refers to plasma, which is a gel-like material in a cell containing various important particles for life.

Thus, sarcoplasmic hypertrophy is an increase in the volume of the fluid and non-contractile components of the muscle (glycogen, water, minerals, etc.).

Here’s a simple visual of how these two types of muscle hypertrophy work:

Bodybuilders have been debating for years whether sarcoplasmic or myofibrillar hypertrophy is more important for building bigger muscles and what training methods best accomplish this, but here’s the bottom line:

Sarcoplasmic hypertrophy probably does play a small, indirect role in promoting muscle growth, but it’s likely more of a beneficial side effect of proper strength training, not an end to pursue in itself.

In other words, by ensuring you achieve myofibrillar hypertrophy, sarcoplasmic hypertrophy will take care of itself.

And how do you maximize myofibrillar hypertrophy? Keep reading to find out.

Summary: Muscle hypertrophy is the scientific term for an increase in muscle size from an expansion in protein, water, or glycogen in your muscles.

Hypertrophy Training vs. Strength Training for Muscle Growth

Spend enough time in the fitness game and you’ll learn that weightlifting is usually divided into two broad categories:

- “Hypertrophy training,” which typically involves higher reps, lighter weights, shorter rest periods, and often involves many isolation exercises and “special” training methods like drop sets, supersets, rest-pause sets, and so forth.

- “Strength training,” which typically involves lower reps, heavier weights, longer rest periods, and focuses most of your efforts on compound exercises like the squat, bench press, and deadlift.

Many people believe that hypertrophy training is better for building bigger muscles (hence the name), while strength training is great for getting stronger but not bigger.

This couldn’t be more wrong.

Hypertrophy Training

Despite what many gymgoers and “gurus” alike claim, the single best way to stimulate muscle hypertrophy is getting stronger.

In other words, strength training (heavy weights and lower rep ranges) is generally better at stimulating muscle growth than “hypertrophy training” (lighter weights and higher rep ranges).

Why?

There are three primary “triggers” or “pathways” for muscle growth:

- Mechanical tension

- Muscle damage

- Cellular fatigue

Mechanical tension refers to the amount of force produced in muscle fibers.

When you lift weights, you produce two types of mechanical tension in your muscles: “passive” and “active” tension. Passive tension occurs when your muscles are stretching, and active tension occurs when they’re contracting.

Muscle damage refers to microscopic damage caused to the muscle fibers by high levels of tension.

This damage requires repair, and if the body is provided with proper nutrition and rest, it’ll make the muscle fibers larger and stronger to better deal with future bouts of tension.

(It’s still not entirely clear whether muscle damage directly stimulates muscle growth or whether it’s just a side effect of mechanical tension, but as of now, it deserves a place on the list.)

Cellular fatigue refers to a host of chemical changes that occur inside and outside muscle fibers when they contract repeatedly. When you repeat the same movement over and over again to the point of near muscular failure, this causes high amounts of cellular fatigue.

Of these three muscle hypertrophy “triggers,” mechanical tension is by far the most important because it produces the greatest growth.

That is, if you want to keep getting bigger and stronger, you want to keep increasing the amount of mechanical tension in your muscles. The process of doing this is known as progressive tension overload or just progressive overload.

There are several ways to achieve progressive overload in your training, but research shows that the most effective one is simply adding more weight to the bar (or dumbbells).

Thus, as strength training is explicitly aimed at improving strength, it follows logically that it should also be the most effective way to gain muscle (as opposed to other types of training that focus on improving muscle endurance or producing big pumps).

And that’s exactly what a growing body of evidence is demonstrating:

Strength training generates large amounts of tension in your muscles, and this produces a more powerful stimulus for muscle growth than traditional hypertrophy training.

This isn’t to say that lighter weights and higher rep ranges have no place in your workout routine (rep range periodization is particularly effective with intermediate and advanced weightlifters, for example), but it should always play second fiddle to strength training.

Read: Is Getting Stronger Really the Best Way to Gain Muscle?

Strength Training

A salient example of the muscle-building power of strength training comes from a study conducted at the University of Central Florida, where scientists separated 33 physically active, resistance-trained men into two groups:

- A hypertrophy training group that did four high-volume, moderate-intensity workouts per week consisting of four sets per exercise in the 10-to-12-rep range (70% of 1RM).

- A strength training group that did four moderate-volume, high-intensity workouts per week consisting of four sets per exercise in the 3-to-5-rep range (90% of 1RM).

Both groups did the same exercises, which included the bench press, barbell squat, deadlift, and seated shoulder press, and both were instructed to maintain their normal eating habits.

After eight weeks of training, researchers found that the second group gained significantly more muscle and strength than the first group.

The scientists suggested two main reasons for why the heavier training beat out the lighter in not only strength gain (not surprising) but muscle gain as well:

1. Higher amounts of mechanical tension in the muscles

The lighter training, on the other hand, caused higher amounts of cellular fatigue.

2. Greater activation of muscle fibers

And this results in greater muscle growth across a larger percentage of the muscle tissue.

Another study published in 2020 by scientists at the University of Campinas found much the same thing—heavy, lower-rep strength training was more effective for promoting muscle hypertrophy than light, low-rep hypertrophy training.

Listen: Research Review: What’s the Best Rep Range for Building Muscle?

This is why your primary goal as a natural weightlifter is to get stronger, and especially on key compound exercises like the squat, deadlift, and bench and overhead press.

In other words, the more weight you can push, pull, and squat, the more muscular you’re going to be.

That’s why my Bigger Leaner Stronger (men) and Thinner Leaner Stronger (women) programs focus on heavy, compound weightlifting (and why these programs are so effective).

Summary: Heavier, lower-rep strength training is generally superior to lighter, higher-rep “hypertrophy” training for building muscle. If you want to get as jacked as possible, get as strong as possible.

The 5 Best Ways to Stimulate Muscle Hypertrophy

While muscle hypertrophy is tremendously complex and scientists are still investigating its many nooks and crannies (and will be for a long time), we know enough to say this:

If you do the following five things, you can gain boatloads of muscle and strength:

- Do a lot of strength training.

- Eat more calories than you burn.

- Eat a lot of protein and carbs.

- Do some cardio.

- Take the right supplements.

Let’s go over each step in turn.

Step 1: Do a lot of strength training.

There are many ways to train your muscles, but when you want to gain size and strength as quickly as possible, nothing beats strength training.

Yes, heavy, compound weightlifting is better for building muscle than workout machines, “pump” classes, home workouts, bodyweight exercises, Yoga, Pilates, and everything else you can do to develop muscle definition.

What do I mean by “heavy, compound weightlifting,” though?

By “heavy,” I mean working with weights in the range of 75 to 95% of your one-rep max (1RM), or 10 to 2 reps per set when ending just a rep or two shy of failure.

And by “compound,” I mean spending most of your time doing exercises that train several major muscle groups, like the squat, deadlift, bench press, and overhead press.

There are a lot of strength training programs that check off these boxes, but I recommend you start with a proven classic routine like push pull legs (PPL), upper/lower, or full body.

Or, you can follow one of the programs in my books for men and women who are new to proper strength training.

Step 2: Eat more calories than you burn.

There’s a lot of truth in the old bodybuilding saw that you have to “eat big to get big.” That said, you don’t have to eat as bigly as many meatheads would have you believe.

Fortunately, a slight calorie surplus of just 5 to 10% is enough to maximize muscle growth without producing too much unwanted fat gain.

That is, if you eat 5 to 10% more calories than you burn every day, you’ll grease the skids of your body’s “muscle-building machinery” and markedly enhance your results.

You know you’ve got it right when you’re gaining 1 to 3 pounds per month if you’re a man, and about half that if you’re a woman, unless you’re new to weightlifting, in which case you can double those numbers for your first three to six months.

After that, however, you should see your weight gain settle into this range.

Not sure how many calories eat to maintain a 5 to 10% calorie surplus? Check out this article . . .

Or having trouble eating enough calories to build muscle? You may want to consider taking a meal replacement supplement, like Atlas.

Step 3: Eat a lot of protein and carbs.

Aside from water, the main component of muscle tissue is protein.

Therefore, for muscle hypertrophy to occur, you need to provide enough of this raw material (protein) for your body to make your muscles bigger and stronger.

How much protein does this process require, though?

One gram per pound of body weight per day is what most research shows is optimal for most people.

After protein intake, your next dietary priority when trying to build muscle as quickly as possible is your carbohydrate intake.

You can read this article to learn why, but the bottom line is you’re going to have a much easier time gaining muscle and strength on a high-carb diet than a moderate- or low-carb one.

That’s why I recommend you start with two grams of carbs per pound of bodyweight per day when lean bulking.

Chances are you’ll need to slowly increase your calories throughout your lean bulk to continue gaining muscle (read this article to learn why), and my preferred method of doing this is simply eating more carbs.

Thus, by the end of lean bulking phase, I’m usually eating upward of 4-to-5 grams of carbohydrate per pound of bodyweight per day.

Step 4: Do some cardio.

You may be surprised to see me recommending cardio for improving muscle and strength gain.

That said, there are several evidence-based reasons to do so:

- Cardio improves insulin sensitivity, which may reduce fat gain while lean bulking.

- Some kinds of cardio, especially those that primarily involve concentric contractions like cycling and rowing, may increase muscle hypertrophy when done alongside strength training.

- Cardio can improve your ability to recover between sets, making for more productive strength training workouts.

- Cardio offers health benefits that you can’t get from strength training alone.

Cardio can also cut into muscle and strength gain, however, especially if you do too much. Thus, here’s what I do and recommend:

- Limit your total weekly cardio time to no more than 50% of the time you spend weightlifting. For example, if you lift weights for five hours per week, don’t do over two and a half hours of moderate- or high-intensity cardio per week.

- Limit your cardio workouts to no more than 30 to 45 minutes per session.

- Choose low-impact types of cardio such as cycling, rowing, elliptical, and swimming over high-impact options like running or plyometrics. This will minimize muscle damage and soreness.

- Keep high-intensity interval training (HIIT) to a minimum and stick mostly to steady-state cardio. HIIT burns more calories per minute than lower-intensity cardio, but it also causes more fatigue, muscle damage, and wear and tear on the body.

If you aren’t sure what kind or how much cardio you want to do, start with two hours of walking per week. This will provide many of the benefits of regular cardio without interfering with muscle growth.

Read: Should You Do Cardio If You Lift Weights? Science Says Yes, and Here’s Why

Step 5: Take the right supplements.

I saved this for last because it’s far less important than proper diet and training.

Remember: supplements don’t build great physiques—dedication to proper training and nutrition does.

That said, although supplements don’t play a vital role in building muscle and losing fat (and many are a complete waste of money), the right ones can help.

Let’s review the best options for building muscle.

Creatine

Creatine is a substance found naturally in the body and in foods like red meat. It’s perhaps the most researched molecule in the world of sport supplements—the subject of hundreds of studies—and the consensus is very clear:

Supplementation with creatine helps . . .

You may have heard that creatine is bad for your kidneys, but these claims have been categorically and repeatedly disproven.

In healthy people, creatine has been shown to have no harmful side effects, in both short- or long-term usage. People with kidney disease are not advised to supplement with creatine, however.

So, if you have healthy kidneys, I highly recommend that you supplement with creatine. It’s safe, cheap, and effective.

In terms of specific products, I recommend Recharge, a 100% natural post-workout drink that boosts muscle growth, improves recovery, and reduces soreness.

Whey Protein Powder

You don’t need protein supplements to gain muscle, but considering how much protein you need to eat every day to maximize muscle growth, getting all your protein from whole food can be impractical.

Whey protein is by far the most popular type of protein supplement out there, because you get a lot of protein per dollar spent, it tastes good, and its amino acid profile is uniquely suited to muscle building.

As for which whey protein to buy, I love Whey+. It’s a 100% naturally sweetened and flavored whey isolate that is made from milk sourced from small dairy farms in Ireland, which are known for their exceptionally high-quality dairy.

Casein Protein Powder

Casein digests slightly slower than whey, providing a steady stream of amino acids to the muscles for growth and repair.

Most scientific research shows both whey and casein are more or less comparable when it comes to building muscle, so which one you choose largely boils down to personal preference.

If you want a great-tasting casein protein powder, try Casein+. It’s a 100% naturally sweetened and flavored casein isolate also made from milk sourced from small dairy farms in Ireland.

Plant-Based Protein Powder

If you don’t eat animal products or want to take a break from whey and casein, you can also get comparable results by taking a high-quality plant-based protein powder.

My favorite is Plant+, a 100% naturally sweetened and flavored blend of pea and rice protein that contains 25 grams of protein per serving.

Pre-Workout Drink

A good pre-workout drink should do a few things for you:

- It should boost your energy levels and motivation to train.

- It should improve your physical performance.

- It should reduce fatigue.

And that’s what you’ll get with Pulse, a 100% naturally sweetened and flavored pre-workout drink that increases energy, mood, focus, strength, and endurance.

The Bottom Line on Muscle Hypertrophy

You can spend hundreds of hours studying muscle hypertrophy and barely scratch the surface.

It’s an extremely complex process that involves scores of physiological functions and adaptations.

Fortunately, you don’t need to be a scientist to have a working understanding of the research, and to use it to build muscle quickly and efficiently.

Here are the key takeaways:

- Muscle hypertrophy is the scientific term for an increase in muscle size, which occurs when the protein, water, or glycogen content of your muscles increases.

- Myofibrillar hypertrophy—an increase in the actual size of your individual muscle fibers— is the primary cause of muscle growth. Sarcoplasmic hypertrophy probably plays a small, indirect role and isn’t a productive end in itself.

- Strength training (heavy weights and lower rep ranges) is generally superior to “hypertrophy training” (lighter, higher-rep work) for building muscle.

And here’s the 5-step plan you need to follow to build as much muscle as possible:

- Do a lot of strength training.

- Eat more calories than you burn.

- Eat a lot of protein and carbs.

- Do some cardio.

- Take the right supplements.

Do that, and you’ll have no trouble building muscle like clockwork.

Happy (lean) bulking!

If you liked this article, please share it on Facebook, Twitter, or wherever you like to hang out online! 🙂

What’s your take on muscle hypertrophy? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Cohen, P. A., Travis, J. C., & Venhuis, B. J. (2014). A methamphetamine analog ( N,α -diethyl-phenylethylamine) identified in a mainstream dietary supplement. Drug Testing and Analysis, 6(7–8), 805–807. https://doi.org/10.1002/dta.1578

- More, S. (2009). Global trends in milk quality: Implications for the Irish dairy industry. In Irish Veterinary Journal (Vol. 62, Issue 4, pp. 5–14). BioMed Central Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-0481-62-S4-S5

- Boirie, Y., Dangin, M., Gachon, P., Vasson, M. P., Maubois, J. L., & Beaufrère, B. (1997). Slow and fast dietary proteins differently modulate postprandial protein accretion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 94(26), 14930–14935. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.94.26.14930

- Tang, J. E., Moore, D. R., Kujbida, G. W., Tarnopolsky, M. A., & Phillips, S. M. (2009). Ingestion of whey hydrolysate, casein, or soy protein isolate: Effects on mixed muscle protein synthesis at rest and following resistance exercise in young men. Journal of Applied Physiology, 107(3), 987–992. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00076.2009

- Norton, L. E., Wilson, G. J., Layman, D. K., Moulton, C. J., & Garlick, P. J. (2012). Leucine content of dietary proteins is a determinant of postprandial skeletal muscle protein synthesis in adult rats. Nutrition and Metabolism, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-9-67

- Francaux, M., & Poortmans, J. R. (2006). Side effects of creatine supplementation in athletes. In International journal of sports physiology and performance (Vol. 1, Issue 4, pp. 311–323). Int J Sports Physiol Perform. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.1.4.311

- Poortmans, J. R., & Francaux, M. (2000). Adverse effects of creatine supplementation: Fact or fiction? In Sports Medicine (Vol. 30, Issue 3, pp. 155–170). Adis International Ltd. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200030030-00002

- Bassit, R. A., Pinheiro, C. H. D. J., Vitzel, K. F., Sproesser, A. J., Silveira, L. R., & Curi, R. (2010). Effect of short-term creatine supplementation on markers of skeletal muscle damage after strenuous contractile activity. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 108(5), 945–955. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-009-1305-1

- Eckerson, J. M., Stout, J. R., Moore, G. A., Stone, N. J., Iwan, K. A., Gebauer, A. N., & Ginsberg, R. (2005). Effect of creatine phosphate supplementation on anaerobic working capacity and body weight after two and six days of loading in men and women. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 19(4), 756–763. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-16924.1

- Branch, J. D. (2003). Effect of creatine supplementation on body composition and performance: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 13(2), 198–226. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.13.2.198

- Helms, E. R., Aragon, A. A., & Fitschen, P. J. (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: Nutrition and supplementation. In Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition (Vol. 11, Issue 1, pp. 1–20). BioMed Central Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-20

- Carvalho, L., Junior, R. M., Truffi, G., Serra, A., Sander, R., De Souza, E. O., & Barroso, R. (2020). Is stronger better? Influence of a strength phase followed by a hypertrophy phase on muscular adaptations in resistance-trained men. Research in Sports Medicine, 00, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438627.2020.1853546

- Mair, J., Mayr, M., Muller, E., Koller, A., Haid, C., Artner-Dworzak, E., Calzolari, C., Larue, C., & Puschendorf, B. (1995). Rapid adaptation to eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 16(6), 352–356. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-973019

- Mangine, G. T., Hoffman, J. R., Gonzalez, A. M., Townsend, J. R., Wells, A. J., Jajtner, A. R., Beyer, K. S., Boone, C. H., Miramonti, A. A., Wang, R., LaMonica, M. B., Fukuda, D. H., Ratamess, N. A., & Stout, J. R. (2015). The effect of training volume and intensity on improvements in muscular strength and size in resistance-trained men. Physiological Reports, 3(8). https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.12472

- Vandenburgh, H. H. (1984). Relationship of muscle growth in vitro to sodium pump activity and transmembrane potential. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 119(3), 283–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.1041190306

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Ratamess, N. A., Peterson, M. D., Contreras, B., Sonmez, G. T., & Alvar, B. A. (2014). Effects of different volume-equated resistance training loading strategies on muscular adaptations in well-trained men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(10), 2909–2918. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000480

- Allen, D. G., Lamb, G. D., & Westerblad, H. (2008). Skeletal muscle fatigue: Cellular mechanisms. In Physiological Reviews (Vol. 88, Issue 1, pp. 287–332). Physiol Rev. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00015.2007

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. In Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (Vol. 24, Issue 10, pp. 2857–2872). J Strength Cond Res. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3

- Acheson, K. J., Schutz, Y., Bessard, T., Anantharaman, K., Flatt, J. P., & Jequier, E. (1988). Glycoprotein storage capacity and de novo lipogenesis during massive carbohydrate overfeeding in man. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 48(2), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/48.2.240

- Forbes, R. M., Cooper, A. R., & Mitchell, H. H. (n.d.). THE COMPOSITION OF THE ADULT HUMAN BODY AS DETERMINED BY CHEMICAL ANALYSIS* Downloaded from. Retrieved December 16, 2020, from http://www.jbc.org/

- Knight, G. S., Beddoe, A. H., Streat, S. J., & Hill, G. L. (1986). Body composition of two human cadavers by neutron activation and chemical analysis. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism, 250(2 (13/2)). https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.1986.250.2.e179