Key Takeaways

- Lower back pain often isn’t caused by a slipped disc or physical damage, but it can still take a long time to go away.

- It can be caused by many different things, but some of the most common causes in athletes are poor form on squats and deadlifts and doing too much, too soon, with too little recovery.

- The best ways to fix lower back pain are to improve your squat and deadlift form, ease into new workout programs, and get enough sleep.

Lower back pain is the bane of athletes everywhere.

About a third of adults deal with it at some point, and that number is even higher for us active folks.

It’s one of the few injuries that almost everyone encounters at some point or another, whether your only activity is pounding away at a keyboard or squatting 500 pounds for reps.

It’s also one of the most mysterious.

Unlike knee, shoulder, and elbow pain, there often isn’t any obvious cause.

Lower back pain can come out of nowhere and stick around for months, disappear, and then suddenly rear its head again with no warning.

This mystery is also why there’s so much pseudoscience, disinformation, and outright quackery surrounding lower back pain.

Some say that it’s all due to poor posture.

Others say that any kind of heavy squatting or deadlifting is bound to “blow out” your back eventually.

And still others say that regardless of the cause, acupuncture, chiropractic, and other alternative treatments are the panacea you need.

Well, in this article, we’re going to get to the bottom of it all.

By the end, you’ll know:

- The most common forms and causes of lower back pain

- How squatting, deadlifting, posture, and core strength affect back pain

- How chiropractic, massage, and acupuncture affect lower back pain

- And more…

At the end, you’ll get a simple, five-step plan for lower back pain relief.

Let’s get started.

What Causes Lower Back Pain?

There’s only one honest answer: We aren’t sure.

This is the key question that’s baffled scientists for years, and many of the things that everyone “knew” caused back pain have since been debunked.

There’s one theory in particular that’s taken hold, though. If you tell someone you have lower back pain, there’s a very strong chance they’re going to tell you the cause is something like this:

- You have a slipped disc

- You have a pinched nerve

- Your hips are out of alignment

- Your core muscles are weak

- You have poor posture

In other words, the usual assumption is that if you have lower back pain, it’s caused by some misalignment or structural problem with your body.

This makes sense at first glance. If something hurts, it must be, well, hurt, right?

Not necessarily.

Physical damage can certainly be part of the problem, but it’s not the whole story.

There are many cases where people have lower back pain with no physical problems, other cases where people have serious physical damage with no lower back pain, and many of the things that are supposed to cause lower back pain aren’t well supported by research.

Let’s look at some of the most common suspects when it comes to lower back pain, and see what the evidence says.

Squatting, Deadlifting, and Lower Back Pain

Squatting and deadlifting are the ultimate scapegoats for lower back pain.

And it’s no wonder why.

Pushing and pulling hundreds of pounds looks like it should be a recipe for spinal disaster.

Thus, many people blame lower back pain on years of heavy squatting and deadlifting. They assume that somewhere along the way, they must have “slipped a disc” or “thrown out” their back.

The basic idea is that back pain is always, or usually, caused by accumulated wear and tear. Often, people use the analogy of bending a credit card. Every rep of heavy lifting is like folding a credit card, and you can only do this so many times before it starts to break.

The heavier and more often you squat and deadlift, the sooner you’ll injure your back, they say.

It’s obvious that you can injure your back from heavy lifting, but is that really the main cause of lower back pain?

Unlikely.

There are two problems with this argument:

- Your back can and does get stronger, not weaker, when you lift weights.

- Obvious damage to the back often doesn’t cause lower back pain.

- When done properly, squats and deadlifts don’t damage your back.

Let’s unpack these arguments.

Your back can and does get stronger, not weaker, when you lift weights.

When people refer to your “back,” what they usually mean are the vertebrae, discs, and muscles, ligaments, and tendons that hold the vertebrae in place.

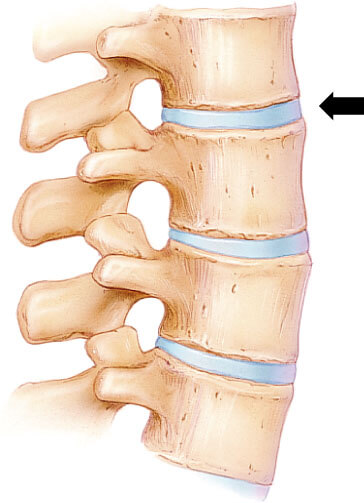

Since they’re considered the most fragile, people usually fixate on the spinal discs. Spinal discs are soft pads of connective tissue filled with a gel-like substance. They act as shock absorbers for the spine and allow the vertebrate to bend and twist.

Here’s what they look like:

Discs do sometimes bulge or even burst (herniate), which can cause pain.

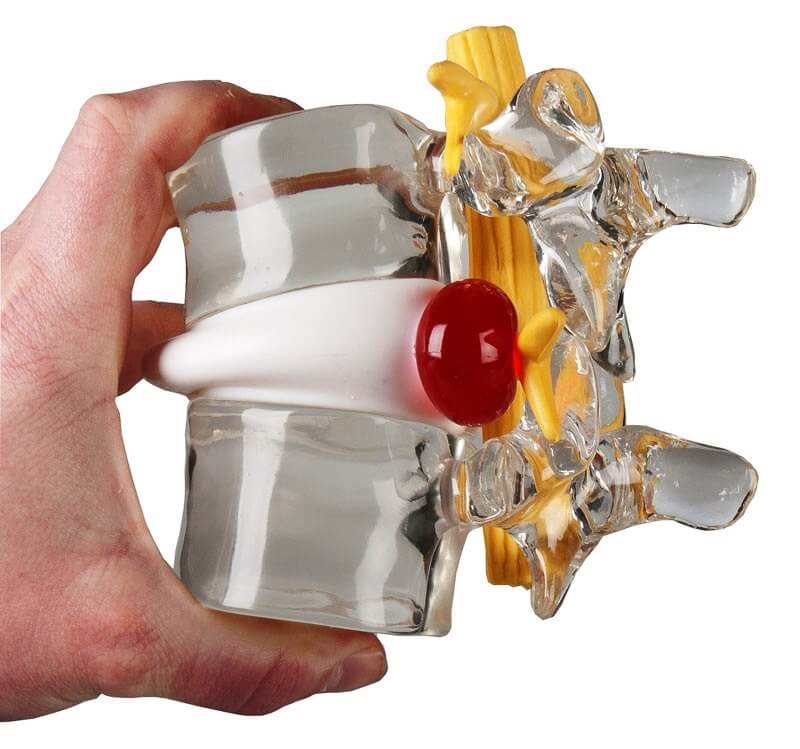

Usually, physical therapists will hammer this point home with a neat little model, like this:

Put too much pressure on those discs, and “pop,” they’ll burst like Gushers.

Thus, it’s only a matter of time before all that heavy squatting and deadlifting ruptures those discs, they say. Plus, all that heavy lifting can pull the vertebrate out of alignment and snap tendons and ligaments, which is what people mean when they say they “threw out” their back.

This can happen, but it’s not as common as many people claim.

First of all, people who lift weights just don’t get injured that often.

For every thousand hours of powerlifting and bodybuilding, you can expect to get about one or two injuries.

To put that in perspective, if you spend five hours per week weightlifting, you could go almost four years without experiencing any kind of injury whatsoever.

For comparison, sports like ice hockey, football, soccer, and rugby have injury rates ranging from 6 to 260 per 1,000 hours, and long-distance runners can expect about 10 injuries per 1,000 hours of pavement pounding.

When injuries do occur, they sometimes involve the lower back, but shoulder, elbow, and hip pain are almost as common.

So, if weightlifting was so bad for your back, then why can people subject themselves to years and years of heavy lifting without getting even a single injury?

Because your lower back (and body) isn’t as fragile as many say.

Heavy weightlifting makes your vertebrate and the connective tissue that holds them in place stronger, not weaker. In fact, many researchers believe that part of the reason that joint pain on the whole is more common nowadays is because people aren’t moving enough.

The bottom line is that on the whole, heavy weightlifting makes your back stronger and more resilient, not weaker.

“Wear and tear” often doesn’t cause lower back pain.

Here’s a fun fact:

By the time you’re 60, there’s about a 9 out of 10 chance you’re going to have some spinal degeneration.

Wom wom.

Now the good news:

Only a small fraction of you will have lower back pain. Sure, you might get some every now and then, but your chances of developing prolonged, constant pain are slim.

Wait a minute… if most people’s backs develop obvious wear and tear by middle to late age, shouldn’t everyone start getting back pain as they age?

Nope.

The reason, is because there’s a very poor correlation between lower back pain and lower back damage.

This was illustrated nicely in a 1994 study published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers found that 64% of people with obvious signs of bulging discs had no back pain. The relationship between herniated discs and back pain was so poor that the researchers concluded that “… bulges or protrusions in people with low back pain may frequently be coincidental.”

In other words, people with lower back pain often have bulging discs, but that’s not why they have lower back pain.

This is buttressed by other research that shows about half of people with visible wear and tear of their spinal discs have no signs of pain. The same thing is true of knee and neck pain, too.

The bottom line is that some wear and tear is a natural, inevitable consequence of not just getting older, but living. The good news is that most wear and tear often doesn’t cause pain and seems to be more or less harmless.

When done properly, squats and deadlifts don’t damage your back.

We’ve all met people who’ve injured themselves throwing around heavy weights.

That doesn’t mean the heavy weightlifting was to blame, though.

If you press these people for details, they’ll often admit something like, “Well, I knew I probably should have stopped, but I really wanted to set a new PR.” Or, “My back felt kind of weird during the warmup, but I decided to keep going anyway.”

Now, there isn’t much evidence to prove that squats and deadlifts are entirely safe, but what little proof we do have shows they probably are (when done correctly).

The first piece of evidence comes from a 2013 study from Goethe-University in Germany. They looked at forces on the knee and lower back during squats with different weights and ranges of motion.

They found that the forces on the spine (and knees) during even heavy, deep squats were well within the safe, healthy limits of the body.

Another study conducted by researchers from the University of Waterloo looked at how much deadlifting flexes the spine and how much strain it put on the vertebrate and lumbar ligaments.

Researchers used real-time x-ray imaging (called fluoroscopy) to watch the spines of elite powerlifters while they fully flexed their spines with no weights, and while they deadlifted over 400 pounds.

With the exception of one person, all men completed their deadlifts within the normal range of motion they displayed during normal, unweighted movement. Ligament lengths were unaffected, indicating that they don’t help support the load, but instead limit range of motion.

In other words, if you’re squatting and deadlifting properly, your lower back isn’t bending or twisting more than when you aren’t using any weights.

When you combine evidence like this against the fact that most powerlifters simply don’t get injured that often, it’s hard to say that squats and deadlifts are bad for your back.

The bottom line is that when done with proper form, and progressed gradually, squats and deadlifts aren’t bad for your back.

Sitting and Lower Back Pain

Poke around online for a few minutes, and you’ll see that sitting is considered one of the worst things you can do for your lower back.

If you’re like most people, including me, you spend a good chunk of your day sitting, and you’ve probably felt some tightness or outright pain in your lower back at some point.

So, this idea jives with many people’s personal experiences.

Of course sitting causes lower back pain. Especially if you shift around in your chair, changing posture, leaning sideways and forward, trying to find a comfortable position.

Well, science says that’s flat out wrong.

One of the best pieces of evidence for this was published in the Scandinavian Journal of Public Health by Danish researchers back in 2000. They looked at 35 different studies on people who were either sedentary or sat most of the day, and found that only one, low-quality study showed an association between low-back pain and sitting.

As the authors concluded:

“The extensive recent epidemiological literature does not support the popular opinion that sitting-while-at-work is associated with LBP (lower back pain).”

Other reviews since then have found the same thing.

A more recent study did find a slight association between lower back pain and sitting in awkward postures and being exposed to vibration (which could happen when operating heavy machinery), but the results were pretty weak and that’s going to be an issue for most.

So, all in all, sitting isn’t associated with lower back pain.

That’s not to say that getting up and moving around every now and then might not help, but sitting for long periods of time doesn’t guarantee you’ll get lower back pain.

Posture and Lower Back Pain

Poor posture just looks… unhealthy.

Surely, hunching over like some gollum wannabe must be bad for your back, shoulders, and knees, right?

Poor posture is also immediately recognizable, easy to fix, and thus, a tempting scapegoat for all kinds of aches and pains.

This is why movement gurus everywhere say that small quirks in your posture, like putting more weight on one leg when you stand, gradually pull your body out of alignment. This forces other parts of your body compensate by altering their movement, which creates a vicious cycle of lower back pain.

If you fix your posture, they say, then everything will fall back into alignment and the pain will go away.

If only it were that easy.

It turns out that all of this is more or less hokum.

There’s very little evidence that small irregularities in posture, movement, or the alignment of your joints increase your risk of any kind of joint pain.

This idea has been thoroughly debunked for knee pain, back pain, and many other kinds of joint pain.

One of the main nails in the coffin for this idea is evidence that people experience pain with no signs of physical injury or “misalignment,” and there are other cases where people have serious structural damage like dislocated vertebrae, but no pain.

Other studies have shown that muscle imbalances and variations in posture also aren’t linked with joint pain.

This isn’t to say that poor posture couldn’t have any effect on lower back pain, but it’s rarely the main cause. There are obviously other reasons to improve your posture, but don’t expect it to heal your lower back pain.

With that out of the way, let’s look at some potential solutions to lower back pain.

Can Chiropractic Treat Lower Back Pain?

Chiropractic is a form of alternative medicine based on fixing misaligned joints, especially the spine, by manually pushing and pulling them back into position.

In theory, realigning joints this way improves the function of nerves, muscles, and other organs in the body.

This theory also seems to be wrong.

In 2012, a Cochrane review (considered one of the most prestigious scientific organizations around), looked at all of the best evidence on chiropractic and back pain.

On the whole, chiropractic wasn’t any better than placebo for treating back pain. Furthermore, it didn’t seem to help at all when it was used in conjunction with other treatments, like physical therapy.

They also found that the vast majority of studies included a high risk of bias, meaning they were poorly designed in a way that makes chiropractic seem more effective than it really is.

Another review in 2017 came to roughly the same conclusion: chiropractic doesn’t work very well for lower back pain.

If we look at the fundamental reason for why chiropractic is supposed to reduce lower back pain, then it looks even less promising. In over 100 years of research, no studies have shown that spinal “subluxations” actually exist or that small variations in spinal movement or structure affect lower back pain.

That doesn’t mean chiropractic is completely worthless, but it’s frequently oversold.

Some studies have found it works about as well as other therapies, so if you’ve tried other treatments with no luck, it might be worth a shot.

Other researchers have also suggested that moving joints through their natural range of motion in a controlled manner could reduce pain through other means, but chiropractic isn’t unique in that regard.

To be fair, many people say that chiropractic helps them feel better, and there’s truth to the idea that, “If it works, it works.” On the other hand, chances are good that any improvement is more likely a placebo effect, so don’t count on chiropractic to actually fix whatever is wrong with your lower back.

The bottom line is that there’s little evidence that chiropractic will reduce lower back pain, and if it does help you feel better, chances are good it was through a placebo effect.

Can Massage Treat Lower Back Pain?

Massage feels good, has very few risks, and is used by many people to reduce pain, but how well does it really work?

Research goes back and forth. Some studies show massage reduces joint pain and others don’t, but on the whole it looks like it’s better than doing nothing.

It’s also hard to say if the (small) benefits of massage therapy are due to the massage, or from a more general improvement in mood.

Massage reduces anxiety and depression, which are both linked with joint pain, so it’s possible that simply feeling better is what makes the pain diminish.

The bottom line is that massage may help reduce your lower back pain and certainly won’t hurt, but it’s far from a sure bet. If you can afford it, it’s probably worth a shot.

Can Acupuncture Treat Lower Back Pain?

Acupuncture is a kind of alternative medicine that involves poking the skin or muscles with extremely thin needles to alleviate pain and to treat various physical, mental, and emotional problems.

Some people say acupuncture works because it “rebalances” the lifeforce of your body, which they call“qi.” Others say it works because it stimulates the body to produce more painkilling chemicals. And others don’t really try to justify why it works.

What do studies show, though?

Well, that acupuncture doesn’t work.

People who get acupuncture for lower back pain get about the same results as people who get a placebo treatment. The best you can expect is a short drop in pain for a few weeks, and even then, the results are so small that they’re almost nonexistent in most cases.

Another problem is that most of the studies on acupuncture are riddled with flaws:

- First, most of the studies are poorly blinded, which means it’s too obvious to either the researchers or the subjects who’s receiving the treatment (and this can skew the results in favor of acupuncture).

- Second, when you’re dealing with pain, providing just about any type of treatment is better than simply doing nothing (thanks to the placebo effect).

- Third, the few positive results are disappointingly small. For example, people who get acupuncture for knee pain typically say their pain improves by 4 points on a 20 point scale, and people who get a placebo treatment say their pain improves by 3 points on a 20 point scale. Not exactly impressive.

At this point, most serious doctors, medical organizations, and pain science researchers don’t recommend acupuncture for lower back pain.

The bottom line is that there’s very little evidence that acupuncture can reduce lower back pain, and in most cases, it’s no better than doing nothing.

The 5-Step Solution for Lower Back Pain Relief

There’s no guaranteed way to cure lower back pain.

Even surgery tends to be unreliable.

That’s why if you’ve been dealing with chronic, unexplained lower back pain, your best bet is to find a good sports physical therapist. Make sure they’re someone who’s dealt with athletes.

If your back pain is more recent or you think it might be caused by your lifting, then the causes and solutions tend to be a bit more straightforward.

In that case lower back pain is usually caused by doing too many reps, or too many sets too quickly, without enough rest.

The solution isn’t necessarily to stop working out altogether, though.

Instead, you’re better off modifying and gradually scaling back your workouts until your lower back feels better.

Let’s go over the checklist for what to do about lower back pain.

Lower Back Pain Solution Step 1

Adjust Your Training Plan

In many cases, you’ll only notice lower back pain on certain exercises or variations of exercises.

If that’s the case, then it’s fine to simply avoid the exercises that hurt until your lower back feels better.

This is what people mean when they say they’re “training around an injury.”

Not only does this let you keep training, but research shows that staying active will probably help your lower back heal faster (so long as none of the activities hurt your lower back).

Here’s how to modify your plan while letting your lower back heal:

1. Replace whatever exercise makes your lower back hurt with a similar variation.

For example, if barbell deadlifts hurt your lower back, try trap-deadlifts.

If your lower back hurts when you low-bar squat, switch to front squats.

If dumbbell lunges are the problem, do single-leg barbell squats.

Overuse injuries are usually caused by performing the same movement over and over, so making little adjustments like these is often all you need to give your lower back a break.

If that doesn’t work…

2. Stop doing all heavy compound lower body exercises.

Heavy, compound lower body exercises are really full-body exercises.

Deadlifts, squats, and lunges train your quads, hamstrings, glutes, lower and upper back, and even your arms to a certain extent.

This is why if one compound exercises starts to cause lower back pain, others can make it worse.

To let your lower back heal, replace your heavy lower body compound lifts with exercises that take stress off of your lower back, like the leg press, leg extension, leg curl, and the like.

If that doesn’t work…

3. Stop doing all lower body exercises.

As much as this sucks, it’s much better than digging yourself into an even deeper hole.

Take at least a month off from lower body exercises or as long as you need to until the lower back pain stops.

If that doesn’t work…

4. Stop lifting weights (until your lower back feels better).

If your lower back hurts so much that most upper and lower body exercises are painful, too, then your best bet for recovering as quickly as possible is to stop lifting weights.

Keep moving as much as you can otherwise, but don’t do anything that hurts.

Some good alternatives are walking, cycling, hiking, golf, rowing, or whatever else you enjoy.

Finally, make sure you aren’t committing any major gym no-nos like skipping your warm up or throwing the weights around with poor form, too.

Lower Back Pain Solution Step 2

Improve Your Lower Body Mobility

Improving your lower body mobility probably isn’t going to directly reduce your lower back pain

It can help, though, if a lack of mobility is keeping you from performing exercises properly.

For example, if your lack of ankle or hip mobility makes it hard to reach proper depth in a squat without rounding your back, then fixing that could reduce your lower back pain.

If you want to learn how to increase your lower body mobility, then check out these articles:

Lower Back Pain Solution Step 3

Increase Your Lower Back Strength

If you aren’t currently lifting weights, and doing so doesn’t hurt your lower back, then you should start.

Strengthening the muscles of your lower back is one of the more reliable ways to reduce and avoid lower back pain, and the same thing is true of other kinds of pain as well.

You need to be careful, though, because if you’re already dealing with lower back pain then more exercise can also make the problem worse.

As you probably know, it’s often hard to tell how hard you should train or how many sets and reps you should do without causing further damage.

This is why it pays to keep track of your lower back pain and adjust your training accordingly.

Here’s how:

- Pick an exercise that you can do to easily test your level of pain. For example, you could do something like Bulgarian split squats, Romanian deadlifts, or back squats.

- Rate your level of pain on a scale of 1 to 10. If the number is a three or less, then go ahead with your workout. If it’s higher than that, stick to exercises that don’t bother your lower back or skip lifting and do a different activity that day.

- Do the same test every day (or every other day, as time allows), at the same time, and track your level of pain. If it gets worse over time, then you need to dial back on your workouts and rest your lower back more. If the pain is the same or less, then you can keep training as much or more than you are now.

If you’d like to learn how to increase your back strength, check out this article:

3 Science-Based Back Workouts for More Hypertrophy, Power, and Strength

Lower Back Pain Solution Step 4

Try Physical Therapy

Physical therapy, also called physiotherapy (PT), involves using exercises, special devices, and education to help people regain or preserve healthy movement.

PT can involve any number of different treatments from massage to special movement exercises to medical devices that reinforce proper movement. Different physical therapists also have different methods and recommend different techniques, so it’s hard to say across the board whether it “works” or not.

If rest doesn’t cut it, though, then PT is worth a shot.

Lower Back Pain Solution Step 5

Take the Right Supplements

Supplements don’t heal injuries. Training properly, eating a healthy diet, and giving yourself enough (but not too much) rest, does.

Most of the supplements that are commonly marketed for joint pain, like glucosamine chondroitin, have also been largely debunked.

That said, there are safe, natural substances that science indicates may help prevent and reduce lower back pain.

Let’s quickly review the supplements that are most likely to help.

Fish Oil

Fish oil is known for being anti-inflammatory, and in cases where lower-back pain is caused by inflammation, taking fish oil may help.

The two main ingredients in fish oil, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), improve the production of anti-inflammatory compounds in the body.

If you eat several servings of fatty fish like salmon, mackerel, sardines, and cod every week, you may not benefit from supplementation with fish oil. If you don’t, however, it’s a good idea to include it in your daily supplement regimen.

And if you’re looking for a high-quality fish oil, then you want to check out Triton.

It’s a high-potency, 100% triglyceride fish oil with added vitamin E to prevent oxidation and rancidity, and natural lemon oil, which prevents noxious “fish oil burps.”

Furthermore, it’s made from sustainably fished deep-water anchovies and sardines and is molecularly distilled to remove synthetic and natural toxins and contaminants.

So, if you want to optimize your mental and physical health and performance and reduce the risk of disease and dysfunction, like shoulder pain, then you want to try Triton today.

Curcumin

Studies show that supplementation with curcumin and black pepper extract reduces inflammatory signals in the joints and, in those with arthritis, relieves pain and stiffness and improves mobility.

When paired with piperine, the clinically effective dosages of curcumin range between 200 and 500 milligrams.

And that’s why there’s 500 mg of curcumin and 25 mg of piperine in each serving of our joint supplement, Fortify.

Fortify contains a clinically effective dose of curcumin in every serving along with three other ingredients also proven to enhance joint health and function:

- Undenatured type ll collagen

- Boswellia serrata

- Grape seed extract

The bottom line is if you want a healthy, functional, and pain-free back that can withstand the demands of your active lifestyle, then you want to try Fortify today.

Undenatured Type ll Collagen

Collagen is the main component of your body’s connective tissues, which means it serves as the primary building block for various things in it, including your skin, teeth, cartilage, bones, and tendons.

The collagen found in supplements comes from the connective tissue in animals, such as cows, chickens, and fish, and while there are over 37 different kinds of collagen in animals, they can be divided into two main categories:

- Type I collagen is the most abundant collagen of the human body, and is present in scar tissue, tendons, ligaments, skin, bones, and more.

- Type II collagen is the collagen that preserves joint function and protects them against damage.

In some cases, your body’s immune system can begin tearing down your own cartilage, in a condition known as arthritis.

Studies show that type II collagen can help alleviate this condition by “teaching” the immune system to stop attacking the proteins in joint cartilage, which in turn can significantly improve joint health and function and decrease or even eliminate pain and swelling.

In other words, type II collagen supplements can work like a natural vaccine of sorts, allowing your body to recognize its own joint collagen as a safe substance, thereby switching off the autoimmune response.

And the best part about type II collagen supplements is that these effects have been demonstrated in people with arthritic conditions and people with healthy joints.

The clinically effective dose of collagen is between 10 to 40 milligrams per day for improving joint health.

That’s a rather large range for dosing, but that’s only because studies have shown benefits using various doses, and it isn’t clear if more is better. Research clearly shows that 10 milligrams is effective, but not that two, three, or four times that amount is necessarily better.

This is why Fortify contains a clinically effective dosage of 10 milligrams of undenatured type ll collagen in every serving.

Grape Seed Extract

Grape seed extract is a substance derived from the ground-up seeds of red wine grapes, which have been used in European medicine for thousands of years.

There are two molecules in grape seed extract that account for most of its health benefits: tannins, which are bitter compounds that make wine taste dry, and procyanidins, which are chains of antioxidants found in some plants.

Much of the research on grape seed extract’s beneficial effects on joint health is extrapolated from research on a similar molecule known as pycnogenol, which is also a potent source of procyanidins. Pycnogenol is significantly more expensive than grape seed extract, however, which is why grape seed extract is preferable for supplementation needs.

The compounds in grape seed extract work by reducing the production of inflammatory compounds in the body, and they also seem to reliably reduce joint pain.

The clinically effective dosage of grape seed extract is 75 to 300 mg per day, which is why Fortify contains 90 mg of grape seed extract per serving.

Boswellia Serrata

Boswellia serrata is a plant that produces an aromatic substance known as frankinsence, which has been used for thousands of years in Ayurvedic medicine to treat various disorders related to inflammation.

Thanks to modern science, we now know why.

Frankinsence contains molecules known as boswellic acids. Research shows that, like curcumin, boswellic acids—and one in particular known as acetyl-keto-beta-boswellic acid, or AKBA—inhibit the production of several proteins that cause inflammation in the body.

And in case you’re wondering, the difference between the anti-inflammatory mechanisms of curcumin and boswellic acids is they work on different enzymes. Curcumin inhibits an enzyme known as cyclooxygenase, or COX, and boswellic acids inbibit lysyl oxidase, or LOX (and, most notably, 5-LOX).

These anti-inflammatory properties extend to the joints, which is why studies show that Boswellia serrata is an effective treatment for reducing joint inflammation and pain as well as inhibiting the autoimmune response that eats away at joint cartilage and eventually causes arthritis.

The clinically effective dosages of boswellia serrata range between 100 and 200 milligrams.

This is why there is 150 mg of boswellia serrata in each serving of Fortify.

White Willow Bark

White willow bark is similar to aspirin (which is a synthetic version of a chemical that’s also found in willow), that’s been used to reduce pain and inflammation for thousands of years.

It works by blocking the production of inflammatory compounds produced in the body, and it works about as well as other NSAIDs.

The clinically effective dosage of white willow bark is 240 milligrams per day.

The Bottom Line on Lower Back Pain

We don’t know exactly what causes lower back pain.

Although many people claim that it’s usually caused by “throwing out” your back or from herniating a disc, the evidence for that is scanty.

Contrary to popular opinion, heavy weightlifting usually doesn’t cause lower back pain or back injuries, if you do it properly. This is even true for the squat and deadlift, which are the usual scapegoats for back pain.

That said, lifting can cause lower back pain if you do too much, too soon, with poor form.

That doesn’t mean you’re doomed, though.

If your lower back has only started hurting recently or seems to hurt off and on with no clear explanation, following these five steps may help:

- Adjust your training plan.

- Improve your lower body mobility.

- Increase your lower back strength.

- Try physical therapy.

- Take the right supplements.

Do that, and there’s a good chance your lower back pain won’t be around for long.

What’s your take on lower-back pain? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- S, C., O, K., A, M., C, C., & A, B. (2001). Treatment of low back pain with a herbal or synthetic anti-rheumatic: a randomized controlled study. Willow bark extract for low back pain. Rheumatology (Oxford, England), 40(12), 1388–1393. https://doi.org/10.1093/RHEUMATOLOGY/40.12.1388

- S, C., E, E., E, B., T, W., R, L., & C, C. (2000). Treatment of low back pain exacerbations with willow bark extract: a randomized double-blind study. The American Journal of Medicine, 109(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00442-3

- N, K., V, T., L, H., & R, K. (2003). Efficacy and tolerability of Boswellia serrata extract in treatment of osteoarthritis of knee--a randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. Phytomedicine : International Journal of Phytotherapy and Phytopharmacology, 10(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1078/094471103321648593

- ER, S., LR, S., B, R., RF, H., HP, A., & H, S. (1996). Acetyl-11-keto-beta-boswellic acid (AKBA): structure requirements for binding and 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory activity. British Journal of Pharmacology, 117(4), 615–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1476-5381.1996.TB15235.X

- MZ, S. (2011). Boswellia serrata, a potential antiinflammatory agent: an overview. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 73(3), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.4103/0250-474X.93507

- P, C., R, J., I, W., K, S., J, M., J, V., Z, D., M, L., & P, R. (2008). Effect of pine bark extract (Pycnogenol) on symptoms of knee osteoarthritis. Phytotherapy Research : PTR, 22(8), 1087–1092. https://doi.org/10.1002/PTR.2461

- DC, C., FC, L., P, S., M, E., N, G., M, B., D, B., DK, D., & SP, R. (2009). Safety and efficacy of undenatured type II collagen in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a clinical trial. International Journal of Medical Sciences, 6(6), 312–321. https://doi.org/10.7150/IJMS.6.312

- M L Barnett, J M Kremer, E W St Clair, D O Clegg, D Furst, M Weisman, M J Fletcher, S Chasan-Taber, E Finger, A Morales, C H Le, & D E Trentham. (n.d.). Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with oral type II collagen. Results of a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial - PubMed. Retrieved August 5, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9485087/

- Bayrak, Ş., & Mitchison, N. A. (1998). Bystander suppression of murine collagen-induced arthritis by long-term nasal administration of a self type II collagen peptide. Clinical and Experimental Immunology, 113(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.1046/J.1365-2249.1998.00638.X

- KL, C., W, S., KR, F., DF, A., F, M., RL, M., JR, D., PS, S., & A, A. (2008). 24-Week study on the use of collagen hydrolysate as a dietary supplement in athletes with activity-related joint pain. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 24(5), 1485–1496. https://doi.org/10.1185/030079908X291967

- Lugo, J. P., Saiyed, Z. M., Lau, F. C., Molina, J. P. L., Pakdaman, M. N., Shamie, A. N., & Udani, J. K. (2013). Undenatured type II collagen (UC-II®) for joint support: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in healthy volunteers. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 10, 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-10-48

- Shoulders, M. D., & Raines, R. T. (2009). COLLAGEN STRUCTURE AND STABILITY. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 78, 929. https://doi.org/10.1146/ANNUREV.BIOCHEM.77.032207.120833

- D, Z., S, O., MW, B., A, G., & D, K. (2015). Collagen peptide supplementation in combination with resistance training improves body composition and increases muscle strength in elderly sarcopenic men: a randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Nutrition, 114(8), 1237–1245. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114515002810

- Y, P., AR, R., M, S., G, A., A, S., & A, S. (2014). Curcuminoid treatment for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Phytotherapy Research : PTR, 28(11), 1625–1631. https://doi.org/10.1002/PTR.5174

- JK, J., T, H., WL, H., & HM, B. (2006). The antioxidants curcumin and quercetin inhibit inflammatory processes associated with arthritis. Inflammation Research : Official Journal of the European Histamine Research Society ... [et Al.], 55(4), 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00011-006-0067-Z

- Maroon, J. C., Bost, J. W., & Maroon, A. (2010). Natural anti-inflammatory agents for pain relief. Surgical Neurology International, 1(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.4103/2152-7806.73804

- P, W., IB, S., O, G., C, H., & K, S. (2010). Effect of glucosamine on pain-related disability in patients with chronic low back pain and degenerative lumbar osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 304(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.2010.893

- Weber, C., Thai, V., Neuheuser, K., Groover, K., & Christ, O. (2015). Efficacy of physical therapy for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12891-015-0665-4

- P, M., J, C., C, P., & E, R. (2015). Patellar Tendinopathy: Clinical Diagnosis, Load Management, and Advice for Challenging Case Presentations. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 45(11), 887–898. https://doi.org/10.2519/JOSPT.2015.5987

- LL, A., M, K., K, S., L, H., AI, K., & G, S. (2008). Effect of two contrasting types of physical exercise on chronic neck muscle pain. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 59(1), 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/ART.23256

- Chang, W.-D., Lin, H.-Y., & Lai, P.-T. (2015). Core strength training for patients with chronic low back pain. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 27(3), 619. https://doi.org/10.1589/JPTS.27.619

- Welch, N., Moran, K., Antony, J., Richter, C., Marshall, B., Coyle, J., Falvey, E., & Franklyn-Miller, A. (2015). The effects of a free-weight-based resistance training intervention on pain, squat biomechanics and MRI-defined lumbar fat infiltration and functional cross-sectional area in those with chronic low back. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 1(1), e000050. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJSEM-2015-000050

- SJ, S. (2006). Achilles tendon rupture: effect of early mobilization in rehabilitation after surgical repair. Foot & Ankle International, 27(6), 407–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/107110070602700603

- KM, K., JL, C., F, B., P, H., & M, A. (1999). Histopathology of common tendinopathies. Update and implications for clinical management. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 27(6), 393–408. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199927060-00004

- Rheum, A., Brox, J. I., Nygaard, Ø. P., Holm, I., Keller, A., Ingebrigtsen, T., & Reikerås, O. (2010). Extended report Four-year follow-up of surgical versus non-surgical therapy for chronic low back pain. Dis, 69, 1643–1648. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2009.108902

- R, C., J, B., EJ, C., DK, R., WO, S., & JD, L. (2009). Surgery for low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Spine, 34(10), 1094–1109. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0B013E3181A105FC

- Manheimer, E., Cheng, K., Linde, K., Lao, L., Yoo, J., Wieland, S., van der Windt, D. A., Berman, B. M., & Bouter, L. M. (2010). Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001977.PUB2

- A, H., & PC, G. (2010). Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2010(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003974.PUB3

- Karanicolas, P. J., Farrokhyar, F., & Bhandari, M. (2010). Blinding: Who, what, when, why, how? Canadian Journal of Surgery, 53(5), 345. /pmc/articles/PMC2947122/

- Casimiro, L., Barnsley, L., Brosseau, L., Milne, S., Welch, V., Tugwell, P., & Wells, G. A. (2005). Acupuncture and electroacupuncture for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003788.PUB2

- Madsen, M. V., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Hróbjartsson, A. (2009). Acupuncture treatment for pain: systematic review of randomised clinical trials with acupuncture, placebo acupuncture, and no acupuncture groups. BMJ, 338(7690), 330–333. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.A3115

- Muhammad Amir Sagheer, Muhammad Farhan Khan, & Salman Sharif. (n.d.). Association between chronic low back pain, anxiety and depression in patients at a tertiary care centre - PubMed. Retrieved August 5, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23901665/

- Christopher A Moyer. (n.d.). Affective massage therapy - PubMed. Retrieved August 5, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21589715/

- TR, W., & D, R. (2016). Myofascial techniques: What are their effects on joint range of motion and pain? - A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 20(3), 682–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBMT.2016.02.013

- A, C., JŠ, B., PJ, T., & MB, R. (2017). Chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy for migraine: a three-armed, single-blinded, placebo, randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Neurology, 24(1), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/ENE.13166

- Zusman, M. (2013). Belief reinforcement: one reason why costs for low back pain have not decreased. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 6, 197. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S44117

- E, E. (2008). Chiropractic: a critical evaluation. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 35(5), 544–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2007.07.004

- Homola, S. (2010). Real orthopaedic subluxations versus imaginary chiropractic subluxations. Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies, 15(4), 284–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.2042-7166.2010.01053.X

- NM, P., IM, M.-L., MS, B., JM, B., AS, M., P, D., R, B., B, T., SC, M., & PG, S. (2017). Association of Spinal Manipulative Therapy With Clinical Benefit and Harm for Acute Low Back Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA, 317(14), 1451–1460. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.2017.3086

- SM, R., CB, T., WJ, A., MR, de B., & MW, van T. (2012). Spinal manipulative therapy for acute low-back pain. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2012(9). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008880.PUB2

- Lun, V., Meeuwisse, W., Stergiou, P., & Stefanyshyn, D. (2004). Relation between running injury and static lower limb alignment in recreational runners. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 38(5), 576. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSM.2003.005488

- Hides J, Fan T, Stanton W, Stanton P, McMahon K, & Wilson S. (n.d.). Asymmetry of psoas and quadratus lumborum unrelated to injury. Retrieved August 5, 2021, from https://www.painscience.com/biblio/asymmetry-of-psoas-and-quadratus-lumborum-unrelated-to-injury.html

- PH, F., LF, B., SC, B., S, H., RJ, P., UJ, H., CM, C., JA, H., RR, E., & MT, S. (2013). Discordance between pain and radiographic severity in knee osteoarthritis: findings from quantitative sensory testing of central sensitization. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 65(2), 363–372. https://doi.org/10.1002/ART.34646

- GL, M. (2012). Teaching people about pain: why do we keep beating around the bush? Pain Management, 2(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.2217/PMT.11.73

- Zusman, M. (2011). The Modernisation of Manipulative Therapy. 2011(05), 644–649. https://doi.org/10.4236/IJCM.2011.25110

- SF, D. (2005). The pathophysiology of patellofemoral pain: a tissue homeostasis perspective. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 436, 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.BLO.0000172303.74414.7D

- Eyal Lederman. (n.d.). Fall of PSB model in manual and physical therapies.

- AM, L., KM, B., H, K., & M, N. (2007). Association between sitting and occupational LBP. European Spine Journal : Official Publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society, 16(2), 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00586-006-0143-7

- EW, B., AP, V., E, van T., C, L., & BW, K. (2009). Spinal mechanical load as a risk factor for low back pain: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Spine, 34(8). https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0B013E318195B257

- SM, C., MF, L., J, C., S, B., & SK, L. (2009). Sedentary lifestyle as a risk factor for low back pain: a systematic review. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 82(7), 797–806. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00420-009-0410-0

- J Hartvigsen, C Leboeuf-Yde, S Lings, & E H Corder. (n.d.). Is sitting-while-at-work associated with low back pain? A systematic, critical literature review - PubMed. Retrieved August 5, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11045756/

- J, C., & SM, M. (1992). Lumbar posterior ligament involvement during extremely heavy lifts estimated from fluoroscopic measurements. Journal of Biomechanics, 25(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9290(92)90242-S

- H, H., K, W., & M, K. (2013). Analysis of the load on the knee joint and vertebral column with changes in squatting depth and weight load. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 43(10), 993–1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-013-0073-6

- D, G., H, F., & AF, M. (2007). The association between cervical spine curvature and neck pain. European Spine Journal : Official Publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society, 16(5), 669–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00586-006-0254-1

- C, L. (2012). Musculoskeletal myths. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 16(2), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBMT.2011.11.003

- MC, J., MN, B.-Z., N, O., MT, M., D, M., & JS, R. (1994). Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. The New England Journal of Medicine, 331(2), 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199407143310201

- S D Boden, D O Davis, T S Dina, N J Patronas, & S W Wiesel. (n.d.). Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation - PubMed. Retrieved August 5, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2312537/

- Hunter, D. J., & Eckstein, F. (2009). Exercise and osteoarthritis. Journal of Anatomy, 214(2), 197. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1469-7580.2008.01013.X

- WL, W. (2012). Resistance training is medicine: effects of strength training on health. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 11(4), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1249/JSR.0B013E31825DABB8

- Videbæk, S., Bueno, A. M., Nielsen, R. O., & Rasmussen, S. (2015). Incidence of Running-Related Injuries Per 1000 h of running in Different Types of Runners: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 45(7), 1017. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-015-0333-8

- Moore, I. S., Ranson, C., & Mathema, P. (2015). Injury Risk in International Rugby Union: Three-Year Injury Surveillance of the Welsh National Team. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 3(7). https://doi.org/10.1177/2325967115596194

- Spinks, A. B., & McClure, R. J. (2007). Quantifying the risk of sports injury: a systematic review of activity‐specific rates for children under 16 years of age. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(9), 548. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSM.2006.033605

- JW, K., & PW, W. (2017). The Epidemiology of Injuries Across the Weight-Training Sports. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 47(3), 479–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-016-0575-0

- U, A., I, S., F, A., & L, B. (2017). Injuries among weightlifters and powerlifters: a systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(4), 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSPORTS-2016-096037

- Brinjikji, W., Luetmer, P. H., Comstock, B., Bresnahan, B. W., Chen, L. E., Deyo, R. A., Halabi, S., Turner, J. A., Avins, A. L., James, K., Wald, J. T., Kallmes, D. F., & Jarvik, J. G. (2015). Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations. AJNR: American Journal of Neuroradiology, 36(4), 811. https://doi.org/10.3174/AJNR.A4173

- Mortazavi, J., Zebardast, J., & Mirzashahi, B. (2015). Low Back Pain in Athletes. Asian Journal of Sports Medicine, 6(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.5812/ASJSM.6(2)2015.24718

- BF, W. (2000). The prevalence of low back pain: a systematic review of the literature from 1966 to 1998. Journal of Spinal Disorders, 13(3), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002517-200006000-00003