It’s estimated that there are over 2+ million scientific papers published each year, and this firehose only seems to intensify.

Even if you narrow your focus to fitness research, it would take several lifetimes to unravel the hairball of studies on nutrition, training, supplementation, and related fields.

This is why my team and I spend thousands of hours each year dissecting and describing scientific studies in articles, podcasts, and books and using the results to formulate our 100% all-natural sports supplements and inform our coaching services.

And while the principles of proper eating and exercising are simple and somewhat immutable, reviewing new research can reinforce or reshape how we eat, train, and live for the better.

Thus, each week, I’m going to share three scientific studies on diet, exercise, supplementation, mindset, and lifestyle that will help you gain muscle and strength, lose fat, perform and feel better, live longer, and get and stay healthier.

This week, you’ll learn the “secret” to keeping weight off when you finish dieting, how risky powerlifting is, and if doing weightlifting while pregnant is healthy.

And the “secret” to weight-loss maintenance is . . .

Source: “Successful weight loss maintenance: A systematic review of weight control registries” published on February 12, 2020 in Obesity Reviews.

Losing weight is tough.

But as anyone who perennially maintains a trim physique will tell you, the real challenge isn’t losing weight but keeping it off.

That’s why most people regain any weight they lose when they finish dieting.

This problem is so prevalent that for the past few decades, scientists at several universities have been gathering information from successful dieters about what helped them lose weight and keep it off.

Recently, scientists at the University of Lisbon pooled and analyzed these weight-loss “registries” to see if they could spot trends that might help others maintain weight loss.

Their results showed that the best strategies for keeping weight off are:

- Having healthy foods available at home.

- Eating breakfast.

- Increasing protein and fiber-rich food and vegetable consumption.

- Exercising regularly.

- Reducing sugary and fatty food consumption.

Among the least frequently reported strategies were following a “special diet,” consuming weight-loss supplements, and, interestingly, receiving professional help from a hypnotist, weight-loss group, or personal trainer.

The results also showed that maintaining weight loss becomes gradually easier, perhaps because the behaviors that ensure successful weight-loss maintenance become habits that demand less conscious effort.

At a time when silver bullets such as fad diets and weight-loss supplements are as popular as ever, these results are a valuable reminder that those who successfully lose weight and keep it off avoid these distractions and focus on what works: following a protein- and fiber-rich diet that’s mainly composed of minimally processed, nutritious foods and regularly exercising.

The only two surprises were the results regarding breakfast and professional help.

Most research shows that breakfast eaters are about as likely to lose weight and keep it off as breakfast skippers, which is why I still think you should eat or skip breakfast based on your preferences.

Likewise, a mountain of evidence shows that seeking diet advice from a qualified professional aids weight loss and maintenance. While the dieters in this study tended not to seek professional help, there’s nothing to suggest it wouldn’t have made their weight-loss journey easier.

For instance, the dieters also identified “emotional eating” (eating to soothe negative emotions) as one of the biggest barriers to enduring weight loss. An effective way to deal with emotional eating is to have contingency plans when emotions strike.

Fathoming these plans alone can be challenging, but they become more manageable with guidance from an experienced coach.

That’s why I think getting help, whether from trusted online sources, podcasts, books, or coaches, is an indispensable tool for ensuring long-lasting weight loss for some people.

(And if you’d like an expert to give you everything you need to build your best body ever, including custom diet and training plans, exercise technique coaching, emotional encouragement, accountability, and more, contact Legion’s VIP one-on-one coaching service to set up a free consultation. Click here to check it out.)

TL;DR: The best ways to ensure long-term weight loss are following a protein- and fiber-rich diet that’s mainly composed of minimally processed, nutritious foods and exercising regularly.

Powerlifting isn’t dangerous.

Source: “Safety of powerlifting: A literature review” published on January 19, 2021 in Science and Sports.

Many people think the “Big 3” are dangerous.

That is, they think squatting thrashes your knees, deadlifting is detrimental to your lower back, and benching banjaxes your shoulders.

You can find plenty of videos of powerlifters injuring themselves, too, but how common is this really?

Are these incidents the exception or the rule?

That’s what scientists at the University of Murcia wanted to puzzle out by reviewing the data from 11 studies involving 763 powerlifters—athletes who spend the vast majority of their training time practicing the squat, deadlift, and bench press.

The results showed that, on average, powerlifters suffer 1-to-4.4 injuries per 1000 hours spent training. The most common injuries in non-disabled athletes were to the shoulders, lower back, hips, and knees, and the shoulders, pectorals, and elbows in paralympic athletes (though this is because the bench press is the sole lift performed in paralympic powerlifting).

To put these figures into perspective, injury rates in soccer (15 per 1000 hours), running, and CrossFit (both ~10 per 1000 hours) are all significantly higher, making powerlifting a relatively safe sport.

How do these numbers relate to the average weightlifter?

Most gym-goers don’t follow programs that are as rigorous as powerlifting programs. For example, my Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger programs for men and women include exercises like the squat, deadlift, and bench press, but these aren’t the sole focus.

This is significant because limiting the time you spend doing these exercises reduces your risk of them causing repetitive strain injuries.

What’s more, programs like Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger don’t involve training as close to your one-rep max as most powerlifting programs, which means they don’t beat up your joints and connective tissues as much, further reducing your risk of injury.

As such, most recreational weightlifters probably have a similar injury rate to bodybuilders, which according to this study, is about 1 injury per ~4000 hours of training.

Even then, you can take steps to reduce your risk further.

If you’re prone to low-back problems, switching to the sumo or trap-bar deadlift instead of the conventional deadlift may help since both variations place less stress on your spine.

Or, if back squatting irritates your knees, try the more knee-friendly front squat. You could also lower yourself slower during the squat. This gives you more control and prevents you from “falling” into positions that stress your knees.

And if your shoulders cry uncle while bench pressing, do the following:

- Tuck your shoulder blades down and squeeze them together for your entire set.

- Use a 1.5 times shoulder-width grip or narrower.

- Keep your elbows at a 30-to-60-degree angle relative to your torso.

- Touch the bar on your chest at nipple height.

- Only do 3-to-6 weekly sets of the flat barbell bench press (this doesn’t mean you can’t do other pressing exercises like the incline bench press, dumbbell bench press, dip, and so forth).

TL;DR: Powerlifters can expect 1-to-4.4 injuries per 1000 hours they spend training, which makes powerlifting significantly safer than soccer, running, and CrossFit.

Weightlifting while you’re pregnant improves blood flow to your baby.

Source: “Acute fetal response to high-intensity interval training in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy” published on August 25, 2021 in Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism.

For many women, pregnancy is not the time for exercise.

Instead, it’s a time for resting, nesting, and prepping for when their baby arrives, all of which, they believe, leaves little time to train.

However, research shows that exercising during pregnancy confers many physical and mental health benefits to both mother and child, before, during, and after birth. That’s why scientists are keen to find ways to make exercising during pregnancy as time-efficient and accessible as possible.

Some believe the answer is high-intensity interval training (HIIT).

HIIT involves repeated bouts of almost all-out exercise interspersed with periods of low-intensity recovery. Generally, it’s performed as cardio, but it can also be done as weightlifting (as it was in this study). One of the main benefits of HIIT workouts is that they’re typically short, which should make them easier to schedule for expectant mothers.

The only problem is that while research shows that HIIT workouts don’t harm an unborn baby (provided you stay below 90% of your maximum heart rate), we know little about how HIIT affects a fetus.

To help clarify this blindspot, scientists at Queen’s University had 14 active pregnant women in their third trimester do 3 rounds of a HIIT-style weightlifting circuit involving the kettlebell swing, banded chest press, goblet squat, dumbbell row, lunge, and Pallof press.

The women did each exercise at near maximum intensity (about an 8 on the RPE scale) for 20 seconds, then took 1 minute of active rest between exercises, during which time they marched in place. Once they’d finished a full circuit, they took 2 minutes of complete rest. The entire workout took 25 minutes and included just 6 minutes of intense exercise.

The results showed that HIIT-style weightlifting had no adverse effects on fetal heart rate or umbilical blood flood. The training also significantly improved blood flow through the umbilical artery, sending more blood and oxygen to the developing baby.

While we’ve known for some time that exercising during pregnancy is healthful, this is the first study to show that HIIT-style weightlifting offers significant benefits to an unborn child. You don’t need to train for long, use specialized equipment, or have much space to get these benefits either, which will hopefully encourage more women to stay active during pregnancy.

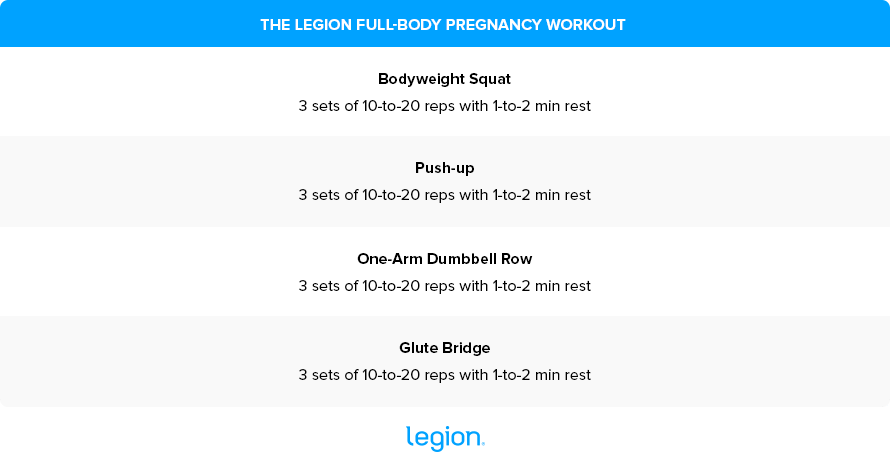

Of course, not everyone can train when they’re expecting, so be sure to clear any training program you undertake while pregnant with your doctor. However, if you’re medically cleared to train during pregnancy, and you want a simple program to keep you and your baby healthy, do the following program on 3 non-consecutive days per week:

TL;DR: HIIT-style weightlifting during pregnancy is safe for mother and child and improves blood flow and oxygen supply to the developing baby.

Scientific References +

- Paixão, C., Dias, C. M., Jorge, R., Carraça, E. V., Yannakoulia, M., de Zwaan, M., Soini, S., Hill, J. O., Teixeira, P. J., & Santos, I. (2020). Successful weight loss maintenance: A systematic review of weight control registries. Obesity Reviews : An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 21(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/OBR.13003

- Nordmo, M., Danielsen, Y. S., & Nordmo, M. (2020). The challenge of keeping it off, a descriptive systematic review of high-quality, follow-up studies of obesity treatments. Obesity Reviews : An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/OBR.12949

- Catenacci, V. A., Ogden, L. G., Stuht, J., Phelan, S., Wing, R. R., Hill, J. O., & Wyatt, H. R. (2008). Physical activity patterns in the National Weight Control Registry. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 16(1), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1038/OBY.2007.6

- Vieira, P. N., Teixeira, P., Sardinha, L. B., Santos, T., Coutinho, S., Mata, J., & Silva, M. N. (2014). [Success in maintaining weight loss in Portugal: the Portuguese Weight Control Registry]. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 19(1), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232014191.2117

- Soini, S., Mustajoki, P., & Eriksson, J. G. (2015). Lifestyle-related factors associated with successful weight loss. Annals of Medicine, 47(2), 88–93. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853890.2015.1004358

- Feller, S., Müller, A., Mayr, A., Engeli, S., Hilbert, A., & De Zwaan, M. (2015). What distinguishes weight loss maintainers of the German Weight Control Registry from the general population? Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 23(5), 1112–1118. https://doi.org/10.1002/OBY.21054

- Karfopoulou, E., Mouliou, K., Koutras, Y., & Yannakoulia, M. (2013). Behaviours associated with weight loss maintenance and regaining in a Mediterranean population sample. A qualitative study. Clinical Obesity, 3(5), n/a-n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/COB.12028

- Paixão, C., Dias, C. M., Jorge, R., Carraça, E. V., Yannakoulia, M., de Zwaan, M., Soini, S., Hill, J. O., Teixeira, P. J., & Santos, I. (2020). Successful weight loss maintenance: A systematic review of weight control registries. Obesity Reviews : An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 21(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/OBR.13003

- Kwasnicka, D., Dombrowski, S. U., White, M., & Sniehotta, F. (2016). Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: a systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychology Review, 10(3), 277–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2016.1151372

- Horikawa, C., Kodama, S., Yachi, Y., Heianza, Y., Hirasawa, R., Ibe, Y., Saito, K., Shimano, H., Yamada, N., & Sone, H. (2011). Skipping breakfast and prevalence of overweight and obesity in Asian and Pacific regions: a meta-analysis. Preventive Medicine, 53(4–5), 260–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YPMED.2011.08.030

- O’Neil, C. E., Nicklas, T. A., & Fulgoni, V. L. (2014). Nutrient intake, diet quality, and weight/adiposity parameters in breakfast patterns compared with no breakfast in adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-2008. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 114(12 Suppl), S27–S43. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAND.2014.08.021

- Van Der Heijden, A. A. W. A., Hu, F. B., Rimm, E. B., & Van Dam, R. M. (2007). A prospective study of breakfast consumption and weight gain among U.S. men. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 15(10), 2463–2469. https://doi.org/10.1038/OBY.2007.292

- Sievert, K., Hussain, S. M., Page, M. J., Wang, Y., Hughes, H. J., Malek, M., & Cicuttini, F. M. (2019). Effect of breakfast on weight and energy intake: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 364. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.L42

- Dayan, P. H., Sforzo, G., Boisseau, N., Pereira-Lancha, L. O., & Lancha, A. H. (2019). A new clinical perspective: Treating obesity with nutritional coaching versus energy-restricted diets. Nutrition, 60, 147–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NUT.2018.09.027

- Silberman, J. M., Kaur, M., Sletteland, J., & Venkatesan, A. (2020). Outcomes in a digital weight management intervention with one-on-one health coaching. PLOS ONE, 15(4), e0232221. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0232221

- Painter, S. L., Ahmed, R., Kushner, R. F., Hill, J. O., Lindquist, R., Brunning, S., & Margulies, A. (2018). Expert Coaching in Weight Loss: Retrospective Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(3). https://doi.org/10.2196/JMIR.9738

- Van Wier, M. F., Arins, G. A. M., Dekkers, J. C., Hendriksen, I. J. M., Smid, T., & Van Mechelen, W. (2009). Phone and e-mail counselling are effective for weight management in an overweight working population: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-6

- Vale, M. J., Jelinek, M. V., Best, J. D., Dart, A. M., Grigg, L. E., Hare, D. L., Ho, B. P., Newman, R. W., & McNeil, J. J. (2003). Coaching patients On Achieving Cardiovascular Health (COACH): a multicenter randomized trial in patients with coronary heart disease. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163(22), 2775–2783. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHINTE.163.22.2775

- Gabriele, J. M., Carpenter, B. D., Tate, D. F., & Fisher, E. B. (2011). Directive and nondirective e-coach support for weight loss in overweight adults. Annals of Behavioral Medicine : A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 41(2), 252–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12160-010-9240-2

- Xiao, L., Yank, V., Wilson, S. R., Lavori, P. W., & Ma, J. (2013). Two-year weight-loss maintenance in primary care-based Diabetes Prevention Program lifestyle interventions. Nutrition & Diabetes, 3(6). https://doi.org/10.1038/NUTD.2013.17

- Tate, D. F., Wing, R. R., & Winett, R. A. (2001). Using Internet technology to deliver a behavioral weight loss program. JAMA, 285(9), 1172–1177. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.285.9.1172

- D, C., S, S., J, L., & W, W. (2015). Successful Medical Weight Loss in a Community Setting. Journal of Obesity & Weight Loss Therapy, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7904.1000248

- O’Hara, B. J., Phongsavan, P., Eakin, E. G., Develin, E., Smith, J., Greenaway, M., & Bauman, A. E. (2013). Effectiveness of Australia’s Get Healthy Information and Coaching Service: maintenance of self-reported anthropometric and behavioural changes after program completion. BMC Public Health, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-175

- Frayn, M., Livshits, S., & Knäuper, B. (2018). Emotional eating and weight regulation: a qualitative study of compensatory behaviors and concerns. Journal of Eating Disorders, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S40337-018-0210-6

- Dudagoitia, E., García-de-Alcaraz, A., & Andersen, L. L. (2021). Safety of powerlifting: A literature review. Science & Sports, 36(3), e59–e68. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCISPO.2020.08.003

- Zebis, M. K., Thorborg, K., Andersen, L. L., Møller, M., Christensen, K. B., Clausen, M. B., Hölmich, P., Wedderkopp, N., Andersen, T. B., & Krustrup, P. (2018). Effects of a lighter, smaller football on acute match injuries in adolescent female football: a pilot cluster-randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 58(5), 644–650. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.17.07903-8

- Videbæk, S., Bueno, A. M., Nielsen, R. O., & Rasmussen, S. (2015). Incidence of Running-Related Injuries Per 1000 h of running in Different Types of Runners: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 45(7), 1017. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-015-0333-8

- Larsen, R. T., Hessner, A. L., Ishøi, L., Langberg, H., & Christensen, J. (2020). Injuries in Novice Participants during an Eight-Week Start up CrossFit Program-A Prospective Cohort Study. Sports (Basel, Switzerland), 8(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/SPORTS8020021

- Miletello, W. M., Beam, J. R., & Cooper, Z. C. (2009). A biomechanical analysis of the squat between competitive collegiate, competitive high school, and novice powerlifters. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(5), 1611–1617. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181A3C6EF

- Fees, M., Decker, T., Snyder-Mackler, L., & Axe, M. J. (1998). Upper extremity weight-training modifications for the injured athlete. A clinical perspective. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 26(5), 732–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/03635465980260052301

- Pratt, N. E. (1994). Anatomy and biomechanics of the shoulder. Journal of Hand Therapy : Official Journal of the American Society of Hand Therapists, 7(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0894-1130(12)80074-3

- Barnett, C., Kippers, V., & Turner, P. (n.d.). Effects of Variations of the Bench Press Exercise on the EMG... : The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/abstract/1995/11000/effects_of_variations_of_the_bench_press_exercise.3.aspx

- V P Kumar, K Satku, & P Balasubramaniam. (n.d.). The role of the long head of biceps brachii in the stabilization of the head of the humerus - PubMed. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2743659/

- M Post, & P Benca. (n.d.). Primary tendinitis of the long head of the biceps - PubMed. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2766599/

- N Madsen, & T McLaughlin. (n.d.). Kinematic factors influencing performance and injury risk in the bench press exercise - PubMed. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6493018/

- Anderson, J., Pudwell, J., McAuslan, C., Barr, L., Kehoe, J., & Davies, G. A. (2021). Acute fetal response to high-intensity interval training in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism = Physiologie Appliquee, Nutrition et Metabolisme, 46(12), 1552–1558. https://doi.org/10.1139/APNM-2020-1086

- Evenson, K. R., Savitz, D. A., & Huston, S. L. (2004). Leisure-time physical activity among pregnant women in the US. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 18(6), 400–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1365-3016.2004.00595.X

- Gaston, A., & Vamos, C. A. (2012). Leisure-Time Physical Activity Patterns and Correlates Among Pregnant Women in Ontario, Canada. Maternal and Child Health Journal 2012 17:3, 17(3), 477–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10995-012-1021-Z

- Zhang, J., & Savitz, D. A. (1996). Exercise during pregnancy among US women. Annals of Epidemiology, 6(1), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/1047-2797(95)00093-3

- Harrison, A. L., Taylor, N. F., Shields, N., & Frawley, H. C. (2018). Attitudes, barriers and enablers to physical activity in pregnant women: a systematic review. Journal of Physiotherapy, 64(1), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPHYS.2017.11.012

- Davenport, M. H., Ruchat, S. M., Poitras, V. J., Jaramillo Garcia, A., Gray, C. E., Barrowman, N., Skow, R. J., Meah, V. L., Riske, L., Sobierajski, F., James, M., Kathol, A. J., Nuspl, M., Marchand, A. A., Nagpal, T. S., Slater, L. G., Weeks, A., Adamo, K. B., Davies, G. A., … Mottola, M. F. (2018). Prenatal exercise for the prevention of gestational diabetes mellitus and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(21), 1367–1375. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSPORTS-2018-099355

- Davenport, M. H., Sobierajski, F., Mottola, M. F., Skow, R. J., Meah, V. L., Poitras, V. J., Gray, C. E., Jaramillo Garcia, A., Barrowman, N., Riske, L., James, M., Nagpal, T. S., Marchand, A. A., Slater, L. G., Adamo, K. B., Davies, G. A., Barakat, R., & Ruchat, S. M. (2018). Glucose responses to acute and chronic exercise during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(21), 1357–1366. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSPORTS-2018-099829

- Davenport, M. H., Marchand, A. A., Mottola, M. F., Poitras, V. J., Gray, C. E., Jaramillo Garcia, A., Barrowman, N., Sobierajski, F., James, M., Meah, V. L., Skow, R. J., Riske, L., Nuspl, M., Nagpal, T. S., Courbalay, A., Slater, L. G., Adamo, K. B., Davies, G. A., Barakat, R., & Ruchat, S. M. (2019). Exercise for the prevention and treatment of low back, pelvic girdle and lumbopelvic pain during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(2), 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSPORTS-2018-099400

- Davenport, M. H., McCurdy, A. P., Mottola, M. F., Skow, R. J., Meah, V. L., Poitras, V. J., Jaramillo Garcia, A., Gray, C. E., Barrowman, N., Riske, L., Sobierajski, F., James, M., Nagpal, T., Marchand, A. A., Nuspl, M., Slater, L. G., Barakat, R., Adamo, K. B., Davies, G. A., & Ruchat, S. M. (2018). Impact of prenatal exercise on both prenatal and postnatal anxiety and depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(21), 1376–1385. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSPORTS-2018-099697

- Davenport, M. H., Meah, V. L., Ruchat, S. M., Davies, G. A., Skow, R. J., Barrowman, N., Adamo, K. B., Poitras, V. J., Gray, C. E., Jaramillo Garcia, A., Sobierajski, F., Riske, L., James, M., Kathol, A. J., Nuspl, M., Marchand, A. A., Nagpal, T. S., Slater, L. G., Weeks, A., … Mottola, M. F. (2018). Impact of prenatal exercise on neonatal and childhood outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(21), 1386–1396. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSPORTS-2018-099836

- Davenport MH, Nagpal TS, & Mottola M. (2020). Correction: Prenatal exercise (including but not limited to pelvic floor muscle training) and urinary incontinence during and following pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(5), e3–e3. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSPORTS-2018-099780CORR2

- Davenport, M. H., Ruchat, S. M., Sobierajski, F., Poitras, V. J., Gray, C. E., Yoo, C., Skow, R. J., Jaramillo Garcia, A., Barrowman, N., Meah, V. L., Nagpal, T. S., Riske, L., James, M., Nuspl, M., Weeks, A., Marchand, A. A., Slater, L. G., Adamo, K. B., Davies, G. A., … Mottola, M. F. (2019). Impact of prenatal exercise on maternal harms, labour and delivery outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSPORTS-2018-099821

- W J Watson, V L Katz, A C Hackney, M M Gall, & R G McMurray. (n.d.). Fetal responses to maximal swimming and cycling exercise during pregnancy - PubMed. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1992404/

- Carpenter, M. W., Sady, S. P., Hoegsberg, B., Sady, M. A., Haydon, B., Cullinane, E. M., Coustan, D. R., & Thompson, P. D. (1988). Fetal Heart Rate Response to Maternal Exertion. JAMA, 259(20), 3006–3009. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.1988.03720200028028

- Salvesen, K. A., Hem, E., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2012). Fetal wellbeing may be compromised during strenuous exercise among pregnant elite athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 46(4), 279–283. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSM.2010.080259

- Szymanski, L. M., & Satin, A. J. (2012). Strenuous exercise during pregnancy: Is there a limit? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 207(3), 179.e1-179.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2012.07.021