It’s estimated that there are over 2+ million scientific papers published each year, and this firehose only seems to intensify.

Even if you narrow your focus to fitness research, it would take several lifetimes to unravel the hairball of studies on nutrition, training, supplementation, and related fields.

This is why my team and I spend thousands of hours each year dissecting and describing scientific studies in articles, podcasts, and books and using the results to formulate our 100% all-natural sports supplements and inform our coaching services.

And while the principles of proper eating and exercising are simple and somewhat immutable, reviewing new research can reinforce or reshape how we eat, train, and live for the better.

Thus, each week, I’m going to share three scientific studies on diet, exercise, supplementation, mindset, and lifestyle that will help you gain muscle and strength, lose fat, perform and feel better, live longer, and get and stay healthier.

This week, you’ll learn if traditional cardio or HIIT is best for burning fat, whether Super Creatine® is more effective than creatine monohydrate, and which muscles shrink the most as you age.

Traditional cardio and HIIT are equally (in)effective at helping you burn fat.

Source: “Slow and Steady, or Hard and Fast? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Comparing Body Composition Changes between Interval Training and Moderate Intensity Continuous Training” published on November 18, 2021 in Sports (Basel).

Over the past few decades, the fitness community has flip-flopped on cardio, at times favoring treadmill walking or jogging for fat loss and at others hailing HIIT as the “shortcut” to burning fat.

This has befuddled many folks who just want to know what kind of cardio they should do to get lean.

A recent meta-analysis conducted by scientists at Solent University settles much of the uncertainty.

The researchers analyzed 54 randomized controlled trials investigating the effects of moderate-intensity steady-state cardio (MISS, which I’ll refer to as “traditional cardio” to keep things simple) and high-intensity interval training (HIIT) on body composition in healthy people.

The results showed that traditional cardio and HIIT were almost identical on every metric the scientists analyzed: Both caused similar fat loss and muscle growth (both trivial), were equally easy to stick to (adherence rate for both was ~89%), and resulted in the same number of injuries (~1 per 1,000 training sessions). There was also no clear indication that some people respond better to one type of training than the other.

These results tell us two things.

First, neither traditional cardio nor HIIT alone is particularly effective at promoting fat loss. For that, you must change your diet. More specifically, you need to eat fewer calories than you burn. (And if you’d like specific advice about how many calories, how much of each macronutrient, and which foods you should eat to lose fat, take the Legion Diet Quiz.)

Once that’s in place, however, doing cardio will likely help you lose fat faster and maintain a lower body weight.

Second, these results show that there’s nothing inherently better about either form of cardio for fat loss.

That said, there are some practical reasons to favor traditional cardio over HIIT. Most people find high-intensity interval training more taxing than low-to-moderate-intensity cardio, especially if they’re doing other forms of exercise like weightlifting, martial arts, endurance sports, and so on. This means HIIT is more likely to interfere with your weightlifting workouts (something you’ll want to avoid if building muscle is a priority).

As such, most weightlifters should prioritize low-to-moderate-intensity cardio and save HIIT sessions for when they’re time-pressed or have some particular reason for boosting their cardio, such as preparing for an event like a Spartan Race.

TL;DR: Moderate-intensity steady-state cardio and high-intensity interval training are equally effective at burning fat, so do whichever you prefer.

Creatine monohydrate is better than Super Creatine®.

Source: “Creatine Monohydrate Supplementation, but not Creatyl-L-Leucine, Increased Muscle Creatine Content in Healthy Young Adults: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial” published on November 1, 2022 in International Journal of Sports Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism.

There’s a new form of creatine on the market, and it knocks the socks off plain ‘ol monohydrate.

That’s what some supplement sellers have been claiming recently.

The “cutting-edge” creatine they’re talking about is creatyl-L-leucine (sold under the name “Super Creatine®”), and to test its alleged superiority, scientists at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign split 29 people into 3 groups:

- A group that took creatine monohydrate

- A group that took creatyl-L-leucine

- A placebo group.

Each group took 5 grams of their designated supplement daily, did 3 weekly weightlifting workouts, and wore an accelerometer to track their activity.

After 14 days, the results showed that all the groups ate about the same amount of food (containing similar amounts of protein, carbs, and fat), did about the same amount of volume in their workouts, were equally active, and gained basically no muscle and a little fat.

The only difference between the groups was that those taking creatine monohydrate increased their muscle creatine stores by ~24%, whereas muscle creatine levels didn’t rise significantly in the creatyl-L-leucine and placebo groups.

A major L for “Super” Creatine®.

The obvious takeaway, then, is that creatine monohydrate is significantly more “super” than Super Creatine®, so stick with monohydrate for now.

Also worth noting is that the creatine monohydrate group topped off their creatine stores after just 2 weeks of supplementing with 5 grams daily. This suggests that, for many people, “loading” creatine (taking 20 grams daily for a week when you first start using creatine) probably isn’t necessary.

Sure, you might have to wait a wee bit longer to see creatine’s benefits, but you also don’t have to choke down 20 grams of creatine per day for a week and potentially upset your stomach in the process.

(If you want a post-workout supplement containing 5 grams of micronized creatine monohydrate that includes two other ingredients to help boost muscle growth and improve recovery, try Recharge.)

Before signing off, there’s one caveat to consider.

Super Creatine® is an ingredient in Bang energy drinks, which is significant because Monster—one of Bang’s biggest competitors—funded this study. Monster also recently sued Bang for claims related to Super Creatine®.

This somewhat weakens this study’s results because it’s possible that financial interests bent the results, but we also don’t know that with certainty.

Despite this, I still think it’s reasonable to assume creatine monohydrate is the best form of creatine on the market. For one thing, it’s been consistently proven to be as good or better than every other form of creatine in terms of benefits and safety for decades. Still, I’ll keep an eye open for research conducted by a disinterested third party before completely writing off creatyl-L-leucine.

TL;DR: Creatine monohydrate is the most effective form of creatine. Take 5 grams daily to boost performance, recovery, and muscle growth.

These are the muscles that shrink the most as you age . . .

Source: “Human skeletal muscle-specific atrophy with aging: a comprehensive review” published on February 24, 2023 in Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985).

Sarcopenia refers to the gradual loss of muscle that occurs as you age.

You can entirely avoid this problem well into your 50s and 60s if you lift weights and follow a high-protein diet, but it will catch up with you eventually. And if you don’t lift weights, you can expect reduced mobility, increased risk of disease and dysfunction, and a decline in your quality of life as you get older.

While we know that sarcopenia affects all areas of the body, we don’t know if some areas are harder hit than others. This is because most studies investigating sarcopenia only measure the quads (mainly because they’re easy to measure).

However, some research suggests that sarcopenia is muscle-group-specific, meaning some muscle groups shrink more than others.

Hypothetically, if you know which muscle groups are the most susceptible to sarcopenia, you could create an exercise plan that emphasizes those “at-risk” muscles and prevents them from getting smaller.

To better understand how sarcopenia affects different muscle groups, scientists at Ball State University compiled the current data into this review.

The researchers pored over 47 studies and compared data about the quads, paraspinals (the muscles that support your back), triceps, biceps, psoas (the muscles that run from your lower spine to the front of your hips), hip adductors, dorsiflexors (the muscles that move your foot and ankle), calves, and hamstrings from 982 young (~25 years old) and 1,003 old (~75 years old) people.

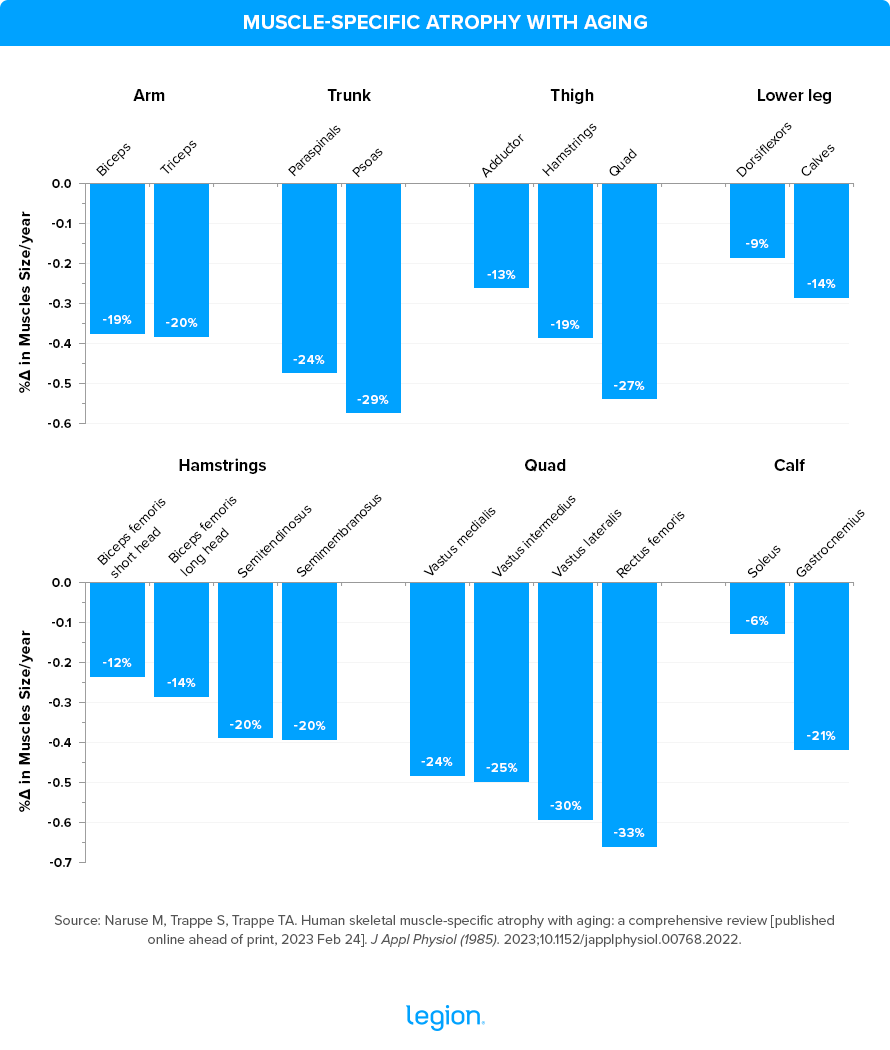

Here’s a graph showing how much muscle the average person loses (expressed as a percentage) between the ages of 25 and 75 years old from each of the muscle groups the researchers investigated:

These findings show that the muscles most affected by sarcopenia are those of the upper legs, lower back, trunk, and arms, which explains why people tend to find walking, stopping, and changing direction (quads and hamstrings), maintaining good posture (paraspinals and psoas), and doing daily tasks, such as showering, cleaning, and lifting heavy objects (upper-arm muscles) more challenging as they get older.

To combat sarcopenia, then, it makes sense to prioritize exercises that train these muscles as we age. And that means emphasizing exercises that involve squatting (which trains the quads, hamstrings, and trunk), hinging at the hips (which trains the hamstrings, lower back, and trunk), and pushing and pulling with the upper body (which trains all of the muscles of the upper body, including the triceps and biceps).

Basically, the results are what you’d expect if you’re familiar with my work and the body of evidence surrounding strength training: you should use compound push, pull, and squat exercises to train your entire body.

Here are some exercises that fit the bill:

- Squat: Back, front, goblet, sumo, or bodyweight squat, Bulgarian or regular split squat, leg press, lunge, and step-up.

- Hip Hinge: Conventional, sumo, trap-bar, or Romanian deadlift, hip thrust, and glute bridge.

- Pushing: Barbell and dumbbell flat and incline bench press, close-grip bench press, standing and seated overhead press, dumbbell shoulder press, Arnold press, dip, and push-up

- Pulling: Pull-up, chin-up, lat pulldown, barbell, dumbbell, and cable row.

And here’s an example of how to put them into a workout that you could do 1-to-3 times per week:

- Goblet squat: 3 sets of 12-to-15 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

- Dumbbell Romanian deadlift: 3 sets of 12-to-15 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

- Push-up: 3 sets of 12-to-15 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

- Lat pulldown: 3 sets of 12-to-15 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

If you like the look of this workout and want an entire fitness program designed to help middle-aged and older people stay fit, healthy, and vital, check out my book, Muscle for Life.

(Or if you aren’t sure if Muscle for Life is right for you or if another training program might be a better fit for your circumstances and goals, then take Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

TL;DR: The muscles that shrink most as we age are the quads, hamstrings, biceps, triceps, and lower back. Make sure your workout program trains these muscles so they stay strong and healthy into old age.

Scientific References +

- Steele, J., Plotkin, D., Van Every, D., Rosa, A., Zambrano, H., Mendelovits, B., Carrasquillo-Mercado, M., Grgic, J., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2021). Slow and Steady, or Hard and Fast? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Comparing Body Composition Changes between Interval Training and Moderate Intensity Continuous Training. Sports (Basel, Switzerland), 9(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/SPORTS9110155

- Swift, D. L., Johannsen, N. M., Lavie, C. J., Earnest, C. P., & Church, T. S. (2014). The role of exercise and physical activity in weight loss and maintenance. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 56(4), 441–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PCAD.2013.09.012

- Thomas, J. G., Bond, D. S., Phelan, S., Hill, J. O., & Wing, R. R. (2014). Weight-loss maintenance for 10 years in the National Weight Control Registry. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 46(1), 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMEPRE.2013.08.019

- Kerns, J. C., Guo, J., Fothergill, E., Howard, L., Knuth, N. D., Brychta, R., Chen, K. Y., Skarulis, M. C., Walter, P. J., & Hall, K. D. (2017). Increased Physical Activity Associated with Less Weight Regain Six Years After “The Biggest Loser” Competition. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 25(11), 1838–1843. https://doi.org/10.1002/OBY.21986

- Askow, A. T., Paulussen, K. J. M., McKenna, C. F., Salvador, A. F., Scaroni, S. E., Hamann, J. S., Ulanov, A. V., Li, Z., Paluska, S. A., Beaudry, K. M., De Lisio, M., & Burd, N. A. (2022). Creatine Monohydrate Supplementation, but not Creatyl-L-Leucine, Increased Muscle Creatine Content in Healthy Young Adults: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 32(6), 446–452. https://doi.org/10.1123/IJSNEM.2022-0074

- Ostojic, S. M., & Ahmetovic, Z. (2008). Gastrointestinal distress after creatine supplementation in athletes: are side effects dose dependent? Research in Sports Medicine (Print), 16(1), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438620701693280

- Naruse, M., Trappe, S., & Trappe, T. A. (2023). Human skeletal muscle-specific atrophy with aging: a comprehensive review. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 134(4). https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.00768.2022

- Hunter, G. R., Singh, H., Carter, S. J., Bryan, D. R., & Fisher, G. (2019). Sarcopenia and Its Implications for Metabolic Health. Journal of Obesity, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8031705

- Larsson, L., Degens, H., Li, M., Salviati, L., Lee, Y. Il, Thompson, W., Kirkland, J. L., & Sandri, M. (2019). Sarcopenia: Aging-Related Loss of Muscle Mass and Function. Physiological Reviews, 99(1), 427–511. https://doi.org/10.1152/PHYSREV.00061.2017

- Grosicki, G. J., Zepeda, C. S., & Sundberg, C. W. (2022). Single muscle fibre contractile function with ageing. The Journal of Physiology, 600(23), 5005–5026. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP282298

- Koopman, R., & Van Loon, L. J. C. (2009). Aging, exercise, and muscle protein metabolism. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 106(6), 2040–2048. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.91551.2008

- Straight, C. R., Fedewa, M. V., Toth, M. J., & Miller, M. S. (2020). Improvements in skeletal muscle fiber size with resistance training are age-dependent in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 129(2), 392–403. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.00170.2020

- Klitgaard, H., Mantoni, M., Schiaffino, S., Ausoni, S., Gorza, L., Laurent-Winter, C., Schnohr, P., & Saltin, B. (1990). Function, morphology and protein expression of ageing skeletal muscle: a cross-sectional study of elderly men with different training backgrounds. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 140(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1748-1716.1990.TB08974.X

- Chambers, T. L., Burnett, T. R., Raue, U., Lee, G. A., Finch, W. H., Graham, B. M., Trappe, T. A., & Trappe, S. (2020). Skeletal muscle size, function, and adiposity with lifelong aerobic exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 128(2), 368–378. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.00426.2019

- Miller, B. F., Baehr, L. M., Musci, R. V., Reid, J. J., Peelor, F. F., Hamilton, K. L., & Bodine, S. C. (2019). Muscle-specific changes in protein synthesis with aging and reloading after disuse atrophy. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 10(6), 1195–1209. https://doi.org/10.1002/JCSM.12470

- Naruse, M., Trappe, S., & Trappe, T. A. (2023). Human skeletal muscle-specific atrophy with aging: a comprehensive review. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00768.2022